Well, not all stress makes us sick. Stress can motivate and energize us—it helps us perform better in front of an audience or get psyched for an adventure, like white-water rafting on the Colorado River in chilly November (shout-out to Mike, Eric, and Frederique!) or skydiving from 13,000 feet (“terrifying” and “freeing” says my brave niece, Laura, pictured).

Well, not all stress makes us sick. Stress can motivate and energize us—it helps us perform better in front of an audience or get psyched for an adventure, like white-water rafting on the Colorado River in chilly November (shout-out to Mike, Eric, and Frederique!) or skydiving from 13,000 feet (“terrifying” and “freeing” says my brave niece, Laura, pictured).

Not surprisingly, skydiving triggers a “fight-or-flight” (literally!) stress hormone response. In one study, 39 men and women who tandem jumped for the first time had increases in cortisol, stress catecholamines, inflammatory cytokines (IL-12 and interferon-gamma), and natural killer cell numbers and gene expression.

Manfred Schedlowski, a German researcher I heard at a conference way back in 1993, found similar results in 45 skydivers. Which intrigued me even then. Who could argue that free-falling from the sky at 120 mph isn’t stressful? Turns out there have been lots of studies since then on the acute stress of those who seek adventure in the skies. Probably because skydiving studies are relatively controllable (a gold standard in scientific studies) and more fun (for the researchers and the subjects) than studying rats getting foot shock, students taking tests, or couples fighting in a simulated environment.

A new finding from this 2016 study was that even short-term stress can change our genes (albeit temporarily). It’s well-known that stress decreases lymphocytes, the white blood cells that fight off viruses like the common cold. Which is why college students often get sick after finals week. But then their immune system bounces back.

When stress becomes chronic and unrelenting—a demanding job, worry about finances, caregiving demands, ongoing health crises—cortisol stays high and our immune cells go into overdrive, spewing out excess inflammatory cytokines, which triggers inflammation and damages DNA, causing irreversible changes in our immune cell genes. And that’s how stress makes us sick.

Telomeres are DNA sequences of genes that sit at the ends of our chromosomes, like the protective caps on shoelaces. They control the lifespan of our cells. When we are stressed, telomeres shorten. The greater the stress, the shorter the telomeres. When telomeres get short, the cell stops dividing and dies. And that’s when we get heart disease, diabetes, immune and autoimmune disease, and Alzheimer’s, because inflammation also affects neurons in the brain.

Aging and disease are a result of the wearing down of telomeres.

In contrast to an acute, short-term, stressful situation, events that are unpredictable, uncontrollable, and/or unrelenting are more likely to trigger maladaptive or chronic stress responses. Our body recovers faster when we have some control, when the event or outcome is perceived as positive (i.e. worth it), and when it is short-term. If you want to skydive, zigzag through rapids, give a TED talk, or travel to a new country, plan for it and go for it! You will build mastery and confidence, and your body will recover.

On the other hand, if you are already feeling stressed by work, finances, family, health demands, or any other situation that is uncertain or unpredictable, then wait for a better time to add additional stress to your life. If you can. So many life events are unpredictable.

Of course, lots of factors, in addition to stress, contribute to age-related illness. There are some things we have no control over—some of us are born with shorter or longer telomeres to start with. And stress doesn’t explain all illnesses, such as disease in young children, but it can make symptoms or the illness worse (such as asthma).

According to co-researchers Elissa Epel, a health psychologist, and Elizabeth Blackburn, a molecular biologist who won the Nobel Prize for discovering telomeres and telomerase, the enzyme that can rebuild telomeres, our telomeres listen to us. Find out how your lifestyle choices and thoughts can help rebuild your telomeres in their surprisingly easy-to-read book, The Telomere Effect (2017). Our thoughts really do influence our genes.

After hearing Dr. Epel talk at a conference on how the chronic stress of caring for a child with cancer shortened mothers’ telomeres, a team of researchers I was working with decided to study if a mindfulness-based stress reduction program (MBSR) could increase telomerase and telomere length in women with breast cancer. We found that a 6-week MBSR program reduced inflammatory biomarkers (cortisol and IL-6) and increased lymphocytes and telomerase activity, but not telomere length. MBSR does reduce stress, but it might take longer than 12 weeks to regenerate telomeres and DNA. Consistent mind-body practices are more likely to protect us from stress.

Dr. Epel advocates exercise as the most powerful antidote to shortened telomeres, along with adequate and restful sleep, an anti-oxidant diet, and mindful responses to stress. Because how we respond is more important than the stressor itself.

Would Laura jump again?

“I would’ve done it ten more times that same day knowing how it felt once you were in the air,” she says, “but ask me again now and no way!”

Her adrenaline has come back to baseline.

I can’t wait to hear how the white-water rafting trip went. I’ll get my adrenaline fix from my friends…for now.

How about you?

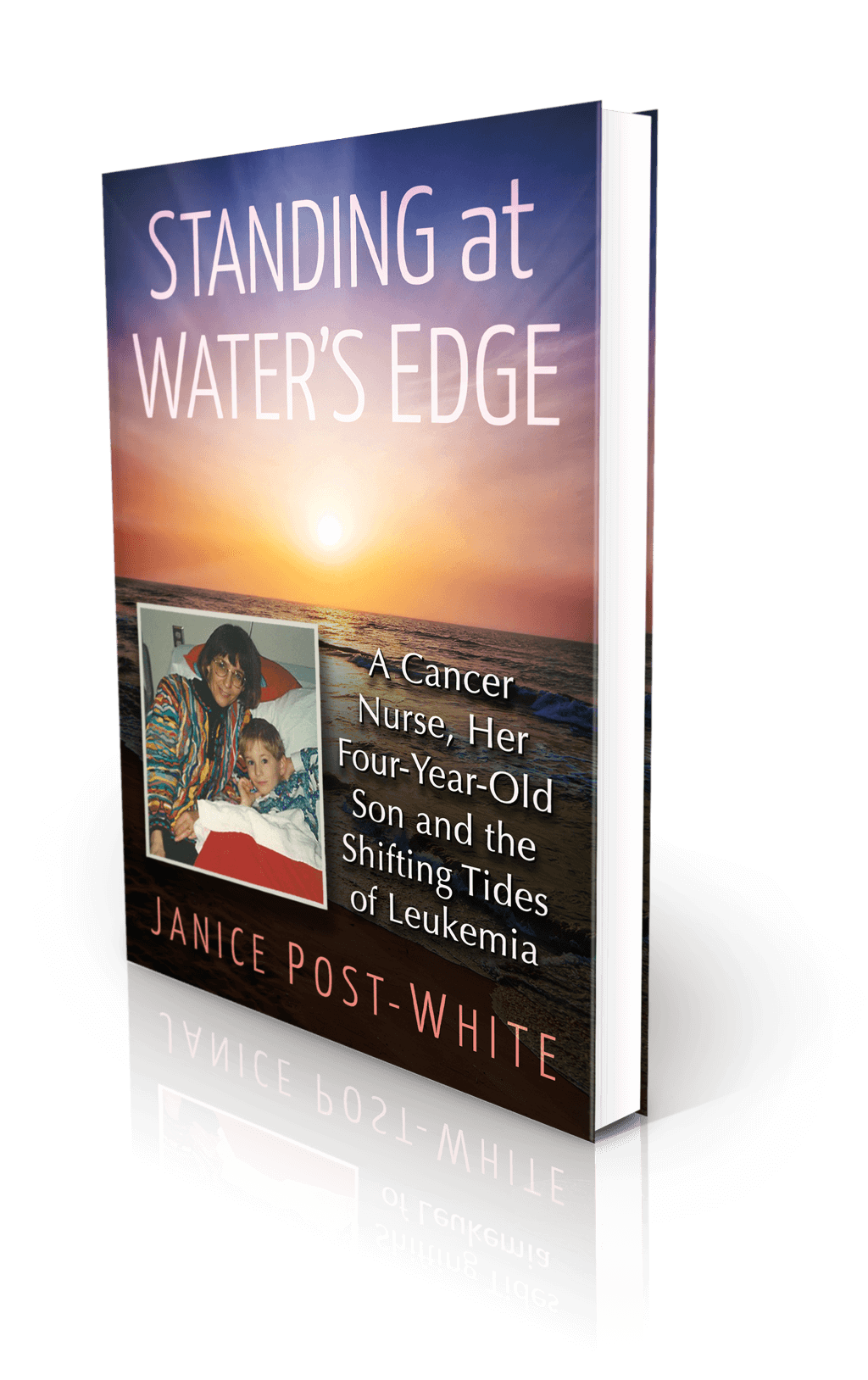

About the Book

Janice Post-White’s memoir is a story about a cancer nurse who thought she knew what life and death were about.

Then her 4-year-old son got leukemia.

This heart-wrenchingly real but inspiring book shines a light on the life-affirming discoveries that can be made when one is forced to face death—and bravely chooses to face fears.

ON SALE DECEMBER 3, 2021

2022 First Place Award from the American Journal of Nursing Book of the Year in the category of Consumer Health and Third Place in Creative Works

Finalist in Health/Cancer from the American Book Fest Best Book Awards, the International Book Awards, and the Eric Hoffer Book Awards