What does it mean to have hope? To expect something positive, meaningful, and affirming. Is everyday hope different from the hope we feel when faced with serious illness or disability?

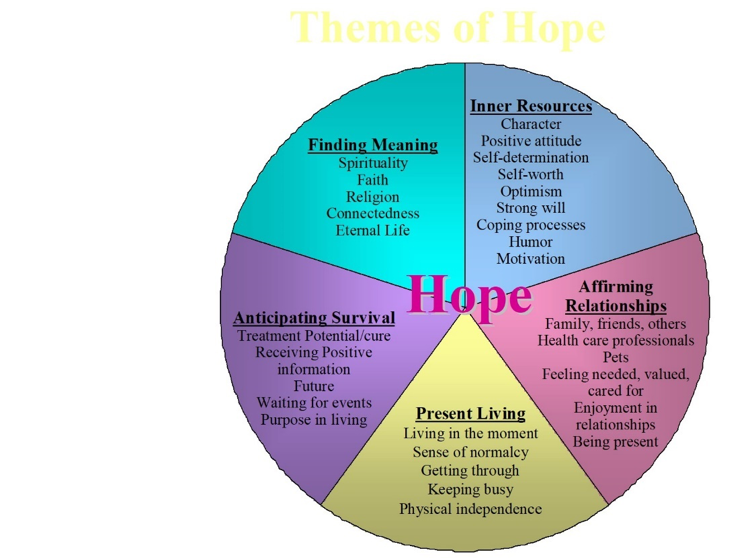

In the year before my son was diagnosed with leukemia, I did a research study asking thirty-two adult patients with cancer what gave them hope. It was a qualitative study—my team interviewed patients four times over eighteen months, and then we analyzed all of the interviews to extract themes and commonalities.

We found five themes, as shown in the figure. The men and women, who were at various stages of treatment and survivorship, found hope by  living in the moment, relying on their own inner resources and strength, receiving support from their loved ones and their health care team, and feeling a spiritual connection to something bigger than themselves. They said they needed to know “that I am not in this alone.” And everyone held out some level of hope of beating the odds, of surviving.

living in the moment, relying on their own inner resources and strength, receiving support from their loved ones and their health care team, and feeling a spiritual connection to something bigger than themselves. They said they needed to know “that I am not in this alone.” And everyone held out some level of hope of beating the odds, of surviving.

This emphasis on survival had surprised me—until my son was diagnosed. Just a few weeks into his treatment, I went to visit a friend and colleague, who was home in hospice care, dying from advanced breast cancer.

“What are the odds?” Kären asked outright.

“Eighty percent of children survive,” I said. “I try not to think about the twenty percent who don’t.”

She nodded as she sat up a bit in her chair, draped in a white blanket, her Irish Setter lying attentively at her feet. “I believed all along that I was in the ten percent who would survive metastatic breast cancer,” she admitted. “It kept me going, believing, having a purpose.”

Similarly, everyone in the study said that having hope gave them the energy to face each day and to move forward with life, despite the uncertainty of how long they would live or how many symptoms they would endure.

But symptoms matter too. It’s tough to feel hopeful when we are sick, hurting, fatigued, or have physical limitations. I’ve only had skin cancer, but I’ve lived with chronic illness all my life. First asthma, then debilitating food and environmental allergies/reactions, immune deficiency, several auto-immune diseases, and more recently, spinal deformities and a spinal cord injury.

It’s hardest to find hope, I find, when the symptoms or limitations are permanent, and especially when they interfere with doing the things I used to enjoy. I enviously watch as my boys, now young men, go out golfing with their dad. Since I was four-years-old, golf was something we did as a family. I played on my high school team, and made it to State, and so did my son.

I can no longer paddle the outrigger canoe—much less hop up in it—with my friend, gliding over the waves in search of spinner dolphins, humpback whales, and enlightening conversation. It’s been three years and my heart aches on every trip to Hawaii. Right now, I’m working on just walking again, and getting back to the beach to sit on the shore and watch as the spinner dolphins jump, the “kids” play football, and the sun sparkles on the midday surf, as if nothing has changed.

I work every day to stay in the moment, focus on what I can do instead of what I can’t, and have hope for tomorrow.

And maybe that’s how we move along the continuum from crisis to coping, from despair to hopefulness. It’s up and down, or back and forth, depending on how you visualize your series. Adapting is rarely linear—more like a roller coaster ride that sometimes feels out of control. The peaks and troughs can leave us feeling sad, stressed, overwhelmed, alone, afraid, and uncertain, which can be immobilizing.

I try to stay focused on baby steps, putting one foot in front of the other. It’s the best advice my patients with cancer gave me. It’s what I did when my son was sick, and it’s what I do now. As with any new experience, we learn by failing—or falling. Isn’t it amazing how babies persist?

How they do eventually find their balance and strength? We can, too. Success encourages us to explore just a little farther next time.

Even if we can’t change our circumstances, we still can find the strength to determinedly put one foot in front of the other and endure, forge ahead, celebrate the little things, and appreciate today.

It’s not what we hope for as much as the life affirming process of hoping that makes us survivors.

Citation: Post-White, J., Ceronsky, C., Kreitzer, M.J., Nickelson, K., Drew, D.,Watrud Mackey, K., Koopmeiners, L., Gutknecht, S. (1996) Hope, spirituality, sense of coherence, and quality of life in patients with cancer. Oncology Nursing Forum, 23(10), 1571-1579. Awarded the 1996/1997 ONF/Chiron Susan B. Baird Excellence in Nursing Research Writing Award.

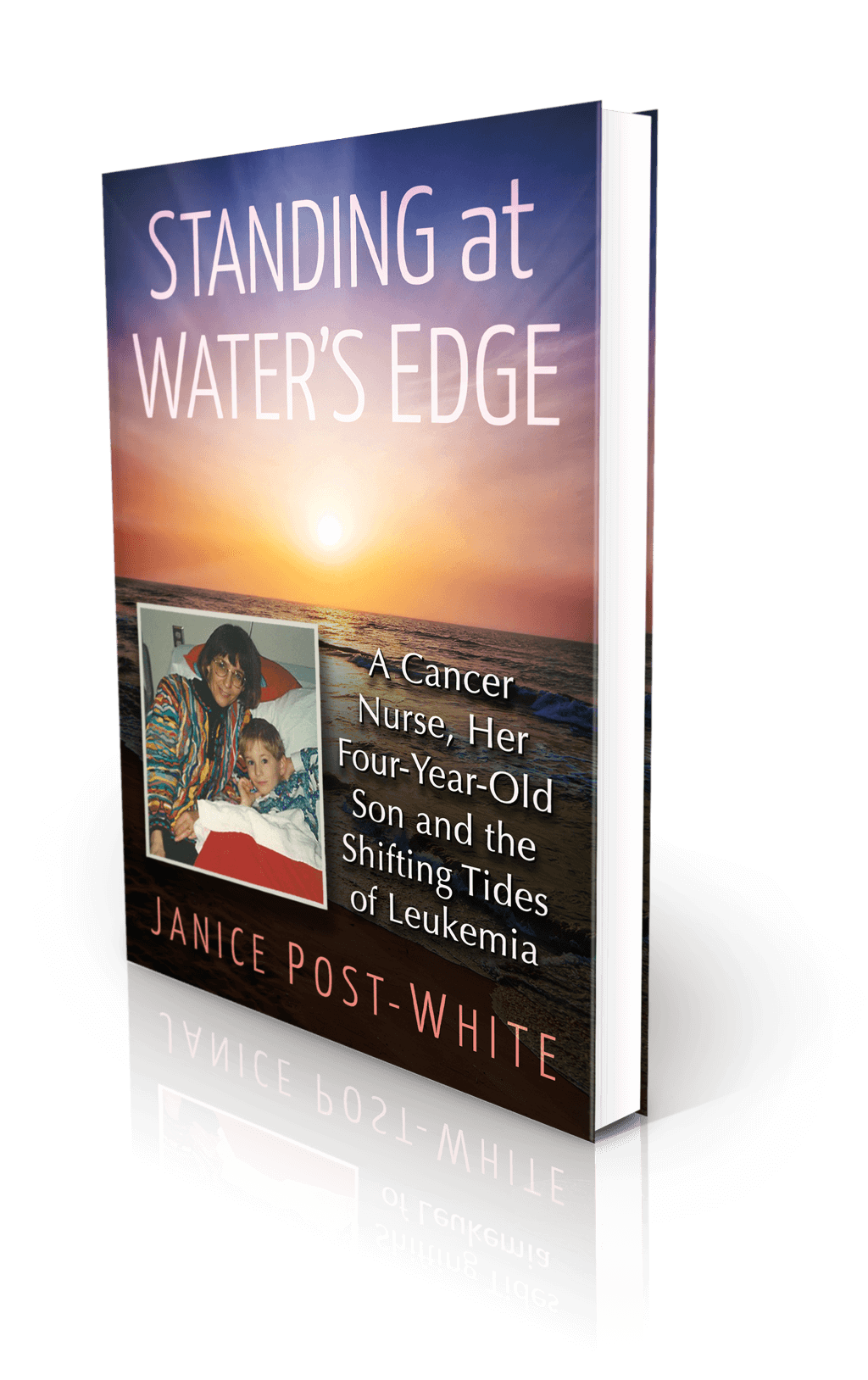

About the Book

Janice Post-White’s memoir is a story about a cancer nurse who thought she knew what life and death were about.

Then her 4-year-old son got leukemia.

This heart-wrenchingly real but inspiring book shines a light on the life-affirming discoveries that can be made when one is forced to face death—and bravely chooses to face fears.

ON SALE DECEMBER 3, 2021

2022 First Place Award from the American Journal of Nursing Book of the Year in the category of Consumer Health and Third Place in Creative Works

Finalist in Health/Cancer from the American Book Fest Best Book Awards, the International Book Awards, and the Eric Hoffer Book Awards