My mother’s 90th birthday is today. I’m giving her an iphone. Shhh…it’s a surprise. Two years ago, I was cautioned by three different salespeople that smartphones are harder for the elderly to learn. She wants to text, and the ABC keyboard is cumbersome. I looked up how to key in spaces, and she used it once, but then forgot. I forgot, too.

It couldn’t be better timing. She’s in lockdown in a small assisted living center in western Wisconsin. We won’t be able to celebrate her milestone birthday with her, as planned, because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Everyone’s disappointed, but she is accepting.

This morning, we dropped off the largest decorated carrot cake our local bakery makes. Staff met my husband at the front door, took his temperature, and collected personal contact information. He waved to his mother-in-law through the window.

Mom celebrated her ninety years on this earth with fellow residents and staff while her family showered her with light and love from different cities, states, and countries. Could you feel it, Mom?

I’m hoping someone will take a picture of her—with her new phone. After they wash their hands for twenty seconds with soap, of course. And then we hope that one of the staff will show her how to Facetime her three remaining children, so that we can share in her spotlight. Afterwards, we might get a thank you or picture by text. That’s a lot to learn in one day, but she’s proved to be tech savvy and motivated. We all have to adapt to stay connected.

When it was still an option to fly, my brother gave her the choice. After explaining the risks of flying and exposing her, he asked, “Do you want us to come now, or stay home and fly up in the summer, if it’s safe then?” She chose to stack the odds in her survival.

“But what if she gets it anyway, doesn’t survive, and we missed the opportunity to see her?” we all ask each other. We may have regrets, but at least we won’t carry guilt.

In a phone call to Mom last week, I mention how Italy, overwhelmed with 6.7% deaths, has had to choose who to save and who to let die. “There aren’t enough ventilators or intensive care beds,” I say. “They can’t treat everyone.” And after a long pause, “They are expecting the same here.” The incidence rate over ten days is eerily predictive.

My mother listens and then says, “I’ve lived a long life, and if it’s my, or our, time to go, that’s in God’s hands, not ours.”

I’m relieved that she included me in her at risk profile. I felt validated.

I had just told my millennial-age son, “If they run out of ventilators, don’t save one for me.” The reality is that, even though I’m not yet 65, I’m high risk and a burden to the healthcare system. With an immune deficiency (I get intravenous immunoglobulin every three weeks), lifelong asthma, rheumatoid arthritis (I take three immunosuppressive drugs), two other autoimmune disorders, and several past pneumonias and repeated bronchitis episodes (all requiring month-long courses of high dose steroids), I don’t have high hopes for sneaking through this pandemic unscathed.

These are hard choices. And I wonder if I’ll really feel as convinced when face to face with such a decision. I want to stay alive for my family and my goals, but I’d rather they, or someone more likely to survive, get the ventilator. One of my sons is a childhood leukemia survivor, the other has asthma and selective immune deficiencies. As a former cancer and bone marrow transplant nurse, I know the risks to immune-compromised persons. I am familiar with reverse isolation to protect the patient and handling of biohazards to protect the staff. It’s a complicated, meticulous process of care that can’t be rushed, or worse, sacrificed.

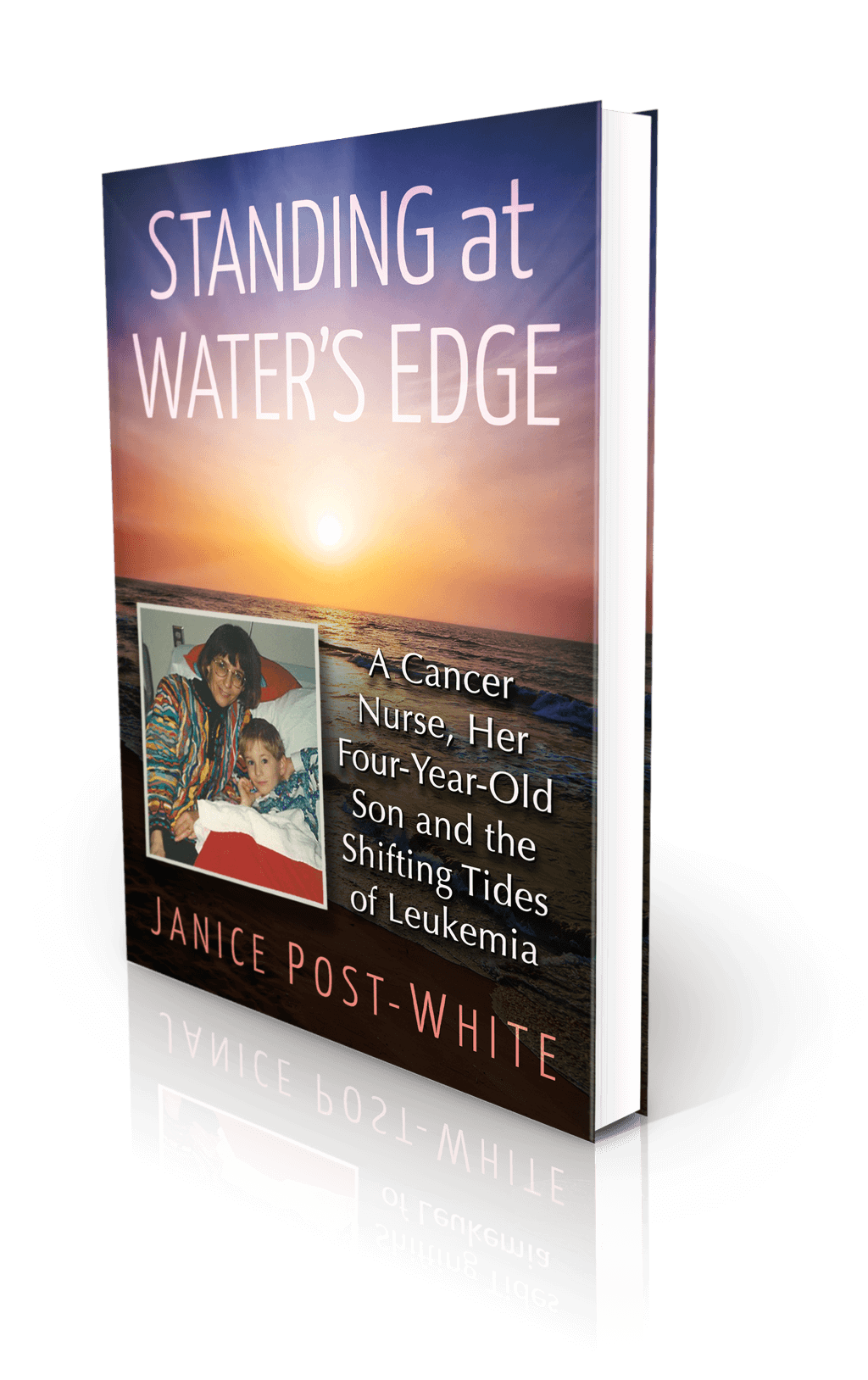

In my memoir, Standing at Water’s Edge: Living Life After Facing Death, I write about how, through my four-year-old’s treatment for leukemia, I came to accept my vulnerability and limitations and let go of my expectations. My cancer patients, fellow parents, and friends taught me how to live in the moment, honor my feelings as much as my knowledge, and accept the uncertainty of life.

When faced with cancer, coronavirus, heart disease, or other life-altering and life-threatening illness, our survival instincts kick in and we are forced to face our mortality. It’s only after the “getting through” survival stage that we make sense of the experience and reflect on what it taught us. We can never go back to “before.” We move on, changed in some elemental way.

COVID-19 will change us. It threatens to be the pandemic of the twenty-first century, just as the Spanish Flu was for the twentieth century. My mother remembers her grandparents talking about how many died. “They already lived in isolation,” she said, “working the farm and land in rural western Wisconsin. They didn’t get sick.”

My mother gets it. If we all comply with social distancing and stay-at-home isolation (except for healthcare and essential workers), she has a better chance of celebrating her birthday with her family this summer, and even making it to her ninety-first.

Thank you for caring about everyone. We may feel isolated, but we are not alone.

May love and light surround you and protect you,

Janice

About the Book

Janice Post-White’s memoir is a story about a cancer nurse who thought she knew what life and death were about.

Then her 4-year-old son got leukemia.

This heart-wrenchingly real but inspiring book shines a light on the life-affirming discoveries that can be made when one is forced to face death—and bravely chooses to face fears.

ON SALE DECEMBER 3, 2021

2022 First Place Award from the American Journal of Nursing Book of the Year in the category of Consumer Health and Third Place in Creative Works

Finalist in Health/Cancer from the American Book Fest Best Book Awards, the International Book Awards, and the Eric Hoffer Book Awards