The weather in Minnesota is as unreliable as the coronavirus reports, as volatile as the stock market, and as uncertain as the likelihood of jobs and normalcy returning to our lives anytime soon. The sun winks at me between low, gray clouds as I close the door with my mittened hand and gingerly head across the parkway for my daily walk. It’s always a slow start as the few nerves in my lower spine that still fire fight for control of the muscles that no longer feel anything. By the time I’ve reached the top of the hill, I’m walking steadier, but the fierce northerly winds steer me away from my intended direction. It starts to snow, and then changes to sleet. I laugh at its temperament. His and mine.

I pause along a new and unfamiliar route, reflecting on the beauty of white confetti on a changing world—little trinkets of hope. As nurses, we used to wear all white.

Just yesterday, I saw fire in the sprint of runners, laughter in the playfulness of pups, joy in the faces of hope. Today, we crouch over, blocking the snow squall that triggers our withdrawal and our fight. It’s early spring in the 44th latitude. It’s the first month of isolation. Anything can happen. I stop to take pictures of the moment.

By the time I reach the lake, six blocks away, the clouds are spraying me with horizontal sheets of hard pellets, like a firehose blasting the flames. I stop to keep my balance, grasping a slender but resilient tree for support, and remind myself to breathe. As I step off the curb, I turn my face away from the sudden onslaught, pull up the collar of my white, down jacket, and tuck my cerulean scarf around my chin, shielding my face from pain and my heart from fear. Sometimes we must look away.

By the time I reach the lake, six blocks away, the clouds are spraying me with horizontal sheets of hard pellets, like a firehose blasting the flames. I stop to keep my balance, grasping a slender but resilient tree for support, and remind myself to breathe. As I step off the curb, I turn my face away from the sudden onslaught, pull up the collar of my white, down jacket, and tuck my cerulean scarf around my chin, shielding my face from pain and my heart from fear. Sometimes we must look away.

I wish then that I had taken a different route. I consider sheltering in place, but there are no leaves on the trees and no cover along the lake. And who knows how long this squall will last? I am vulnerable in the open storm.

I wave and call “good luck!” to the couple walking briskly toward me, their faces covered, and their strides determined, as we each veer off the walking path onto either side, as if we have been doing this forever. I continue on, facing the searing blasts as I zig-zag back up the hill toward the shelter of home.

I think of my father, whom we buried ten years ago this week. It was Easter week then, too. He had lived for thirteen years with fifty percent of his heart pumping, after being resuscitated in the emergency room. In that time, he survived two lung cancer surgeries, ten years apart, and weathered through the pain of blood clots in his heart, abdomen, and legs.

He died in the wee hours of Maundy Thursday, a full moon blazing a deep, golden orange through the picture window of the care facility. As I watched the huge sphere slowly rise above the horizon, I gently placed my right hand on his chest, and said to him through the drug-induced haze of Ativan, “The moon is huge, Dad. It’s right outside your window, beaming in.” I paused, feeling warm energy flow through me. “You know, Dad, the courage in your heart is like the full moon growing bigger over the horizon, rising bravely into the sky.”

For thirteen years, my strong and athletic father had adapted his life, his activities, his hopes and his dreams. His limitations redefined his identity, as chronic illness does. And yet he persisted, as long as his life held meaning, purpose, and hope.

I wish I would have asked him what made him hold on. I suspect that some of it was fear—fear of death, fear of dying alone, fear of leaving behind those who needed or loved him. I saw it in his eyes, I heard it in his words, I felt it in my heart. And then, on a late February stay in the cardiac care unit, he made the decision to stop his heart medications. All of them. Three times, with three different doctors. He didn’t google what would happen. How he would die. He didn’t read stories of others’ suffering. He trusted—and listened to—his own heart as it led him forward.

In his dying, my father taught me courage.

In his dying, my father taught me courage.

What are you afraid of? What gives you the strength to face your fears?

The practice of Tonglen advises us to breathe in the fear, the suffering. To acknowledge it, honor it. And then to breathe out love, compassion, trust, faith. Breathe out whatever it is you want to feel in your heart and share with the world. Breathe in to receive; breathe out to send.

I breathe rhythmically, meditatively, as I reach the peak of the hill. I breathe out joy as I think of my father’s ethereal presence two hours after his passing. I walked through the house at five a.m. singing “Joy, joy, joy,” knowing he was at peace.

The winds have calmed, but I quickly turn and follow my well-known path back down the hill toward home. I seek comfort and warmth—even isolation—feeling battered by the battle. It’s only weather, I laugh, as the clouds race across the sky. I open the door to the kitchen, bright sunlight streaming in.

We can’t know what will happen—or how we will feel—when we emerge on the other side of spring, of COVID-19, of life. Survival is about getting through, but hope springs eternal.

Blessings for a joyous Easter, a hope-filled Passover.

Janice

About the Book

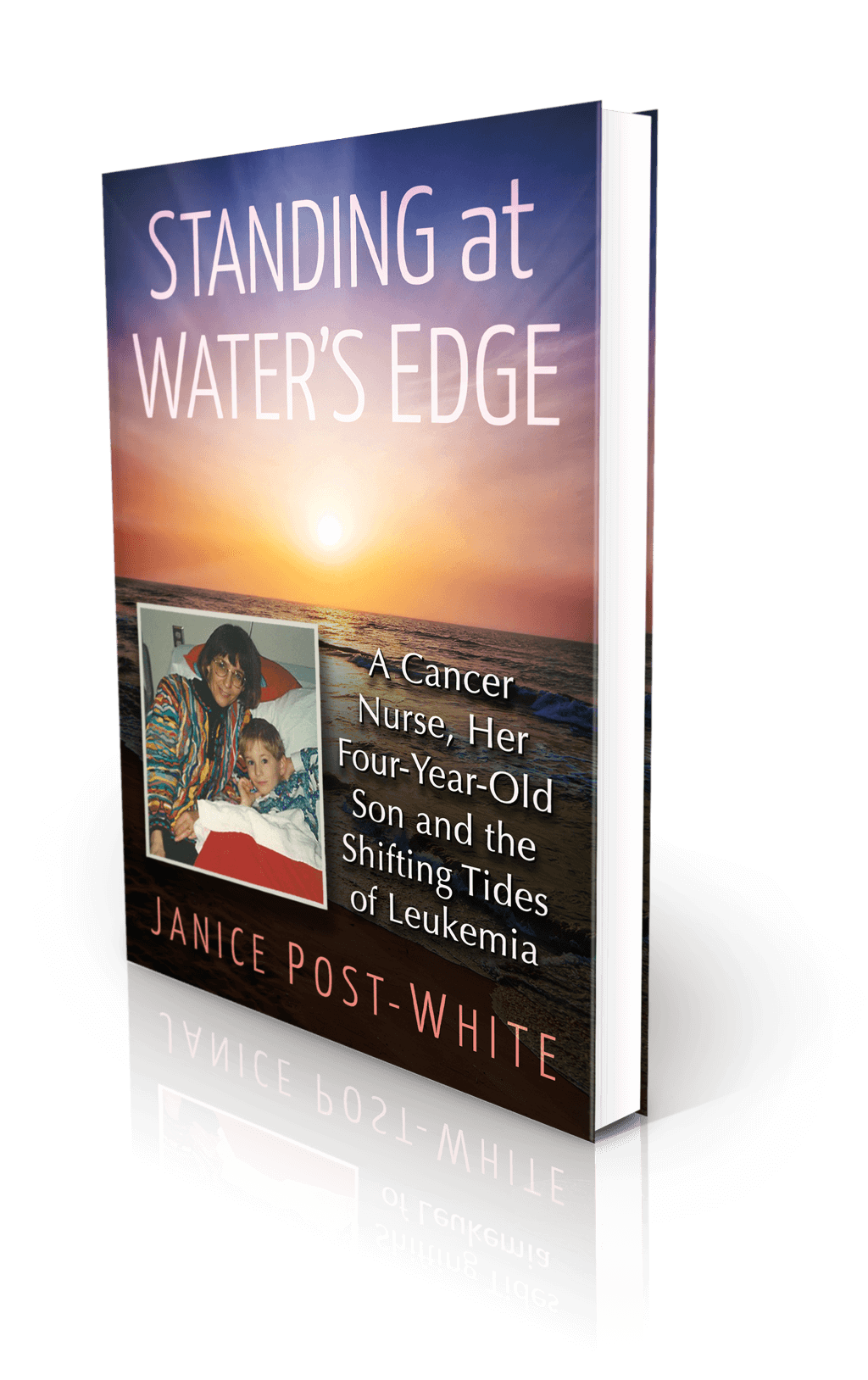

Janice Post-White’s memoir is a story about a cancer nurse who thought she knew what life and death were about.

Then her 4-year-old son got leukemia.

This heart-wrenchingly real but inspiring book shines a light on the life-affirming discoveries that can be made when one is forced to face death—and bravely chooses to face fears.

ON SALE DECEMBER 3, 2021

2022 First Place Award from the American Journal of Nursing Book of the Year in the category of Consumer Health and Third Place in Creative Works

Finalist in Health/Cancer from the American Book Fest Best Book Awards, the International Book Awards, and the Eric Hoffer Book Awards