Today’s guest post is by Podcaster Brennan R. White @Explainthenews. To listen to the podcast, go to Podcasts – Explain The News.

Vaccine hesitancy, istock photo

With COVID-19 vaccination rates falling for the first time, and supply beginning to outpace demand in the United States, the quest for herd immunity is getting more difficult. Twenty percent of the country is reportedly hesitant—but potentially willing—to get vaccinated. What are their reservations, and what will help them overcome their hesitancy?

As of today, 54 percent of adults in the United States have received at least one vaccine dose, and 37 percent are fully vaccinated. Recent polling suggests that just 60 percent want to get vaccinated, so at the current rate, everyone who is interested will have begun the vaccination process by the end of May. This is a tremendous accomplishment. President Biden’s promise of 200 million administered doses in his first 100 days in office was met with weeks to spare and is a testament to the healthcare infrastructure, even if there were some hiccups along the way.

However, as 60 percent of vaccination success approaches, demand is beginning to decrease. With the government having procured hundreds of millions of excess doses, distributors and providers now face the difficult task of convincing those who are hesitant to get vaccinated, or else those doses could be sent somewhere else (like India) to avoid being thrown away.

The remaining 40 percent of adults are equally split into two camps—people who are hesitant about getting vaccinated and people who refuse to get vaccinated. Notably, the percent of refusers has decreased from 35 percent to 20 percent over time, so there is certainly room for continued progress as it becomes more evident that the vaccines are largely both safe and effective, and in some places, might be required to return to normal life. But the 20 percent of hesitant people will likely dictate if and when the country reaches herd immunity.

Herd Immunity

Herd immunity is the concept that when enough people are immune, the entire group will be protected, even the people who are not immune themselves. It works by denying the virus the opportunity to spread and varies based on how contagious a disease is. Once a certain threshold proportion of a population is immune, an infected individual will infect less than one other person on average, and the spread will decline to zero over time.

Nobody knows exactly what percentage of people will need to be vaccinated to reach herd immunity for COVID-19, partly because of many other viral and personal variables to consider. However, given that 32 million people have been infected, the current estimates are that between 70 to 80 percent of the population needs to get vaccinated. To be clear, herd immunity isn’t binary—there isn’t a number where the whole country goes from vulnerable to immune. Even if we don’t reach 70 percent, the closer we can get, the better, and if we do reach 80 percent, that doesn’t mean we should stop vaccinating people. In fact, as the percentage of vaccinated people rises, each new person that chooses to get vaccinated is more important than the last, as they account for a larger percentage of the remaining unvaccinated population.

A growing number of public health officials are publicly resigning themselves and the rest of the country to the fact that herd immunity might be unattainable. Children under sixteen still can’t get vaccinated, the duration of immunity granted by vaccines or the virus itself is unknown, and the longer the process takes, the greater the threat of vaccine-resistant mutations becomes. Normalcy is still attainable without herd immunity, even if it comes with COVID-19 as a new endemic virus, but it still requires a significant portion of the populace to be vaccinated. No matter what the end game looks like, the vaccine-hesitant group will play an important role.

Herd Immunity, photo by istock

Vaccine Hesitancy

So why are people hesitant? The first thing to remember is that this one is not a monolith like any other demographic group. Many people have multiple concerns, and some may overlap.

Factors influencing vaccine hesitancy:

- Safety (will it harm me)

- Efficacy (does it work)

- Distrust in government or healthcare industry

- Politicization

- Second dose considered inconvenient or unnecessary

- Media slant

The most common concern is that the vaccines aren’t safe. This belief encompasses everything from concerns about long-term side effects to conspiracies about autism, microchips, and DNA editing. The number of people citing safety as their main concern has fallen over time as more and more people are vaccinated without issue.

However, the recent decision to pause the distribution of the Johnson and Johnson (J&J) vaccine may have serious consequences. In a recent poll, two-thirds of people who identified as hesitant said that the decision to pause the J&J vaccine negatively impacted their confidence in vaccine safety overall, despite an attempt by the Biden administration to spin the decision as pro-safety. Now that the pause has been lifted, 75 percent of unvaccinated people in the U.S. say they will not take the J&J vaccine, raising doubts about its future viability. That doesn’t necessarily mean the pause was the wrong decision. It’s possible other actions could have been interpreted as a cover-up and received more backlash, but to combat safety concerns, public health officials should consider how hesitant individuals might interpret their decisions and work with the media to communicate better their rationale and the actual risk identified.

Ultimately, safety concerns will best be addressed over time and with better education. In some cases, they might be weak enough that other incentives can overcome them. If people are offered a reward or required to be vaccinated to travel or attend large gatherings, they might begin to view safety concerns as one piece of a larger puzzle, where the benefits outweigh the perceived risk.

Relatedly, many people also are concerned about the efficacy of the vaccines. This often goes hand in hand with a belief that COVID is not a serious threat. Why get vaccinated if you think you’ll be fine if you get sick and you’re not even sure if the vaccine works? From a statistical perspective, vaccines are highly effective, more so than anyone could have hoped for a year ago, which is why the most common way to dispel concern over efficacy is to remind people of that fact.

The Odds of Getting Struck by Lightning

Recently, the CDC—and subsequently several news outlets—have compared the odds of being hospitalized with COVID-19 after getting vaccinated to the odds of being struck by lightning in any given year. But this approach misses the point on two levels. First, it doesn’t address the belief that “COVID won’t affect me.” Even if the vaccines were 100 percent effective, it doesn’t matter if you believe that what they’re protecting you from won’t impact you.

The reason the focus is on the benefit is that the cost is a lot harder to prove. COVID-19 is dangerous, anyone can get it, and anyone can die from it. Many people get miserably sick, the long-term effects are a legitimate concern, and the public health cost of potentially spreading it to others is often overlooked. But many people, especially young people, really are unaffected, and it’s not hard to talk yourself into thinking that you’ll be one of those people. Add on the fact that a lot of people feel in control of their chances of becoming infected, and you start to see why a large swath of the population is able to ignore the dangers of a virus that’s killed almost 1 in 500 people.

The second reason the lightning strike analogy doesn’t work is that it’s an irrational fear. Think of COVID as a constant thunderstorm. You can stay sheltered most of the time and likely be fine, but at some point, everyone has to go into the thunderstorm and risk being struck by lightning. A vaccine is a lightning-resistant suit, and all you have to do is pick one up for free at a nearby store. But the suit is only 95 percent effective. When it does fail, people typically get a small electric shock, but on rare occasions, they die.

So far, you’ve been navigating this storm just fine without a suit, but you think it might be a nice thing to have; you’re just not convinced it’s actually 95 percent effective. It doesn’t help that every time someone in a suit dies from a lightning strike is front and center in the news. Or that some people get hospitalized or die from an allergic reaction to the suit. That’s also in the news. Oh, and by the way, the suit isn’t available near you, and it’s not very pleasant the first few days you wear it. And maybe someone you know who wears a suit still got struck by lightning. At that point, you might not be anti-suit, but you’re not exactly eager to go out of your way to get one.

How to Change Vaccine Hesitancy

Concerns about efficacy can’t be approached the same way as concerns about safety. Someone concerned about safety is more likely to go from being hesitant to refusing the vaccine because the benefits don’t matter if the cost is severe enough. Therefore, the best approach is education.

For people concerned about efficacy, it’s more effective to lower the cost. Make it really easy to get vaccinated—as easy as it is not to get vaccinated. Vaccinate people where they are, whether at home, at work, or in their community. Let them get it whenever it works best for them, let them choose the vaccine brand they want, and don’t make them wait. If necessary, throw in another incentive to increase the benefit. If they think the benefit of vaccination is extremely low, then the cost of getting it has to be even lower.

The next most-cited concern about vaccination is the potential side effects. People don’t want to have to deal with the annoyance of a sore arm, minor headache, and fatigue, much less the rarer allergic reactions, blood clots, or other severe symptoms. These costs are very real, and some of them are likely, especially if you get two doses.

Most people are willing to endure the cost of minor symptoms because they think it’s better than having COVID itself, and it’s just the cost of getting back to a normal life. But if you’re someone who’s already doing what you normally would and don’t think you’ll get COVID anyway, or if you do get it and believe it’s not that bad, why subject yourself to those relatively minor side effects? It doesn’t help that these effects are immediate and can be tied directly to a decision you made.

This is where incentives work best. In this case, the cost is relatively fixed, so if the benefit of COVID immunity isn’t enough, there will have to be another reward. It seems like we’re quickly approaching the point where something like a $100 reward could get us past the 70 percent threshold. The obvious arguments against this are cost and fairness. It would cost just over 1 billion dollars to incentivize 5 percent of adults to get vaccinated. But if it was marketed correctly, the people who have already been vaccinated might not be too upset that they missed out because they get to return to a normal life as a result. Obviously, any plan would need to take effect immediately so as not to incentivize people to wait longer, but don’t be surprised if at some point in the future, another incentive enters the picture as we near 70 percent.

Distrust in government and healthcare institutions is much harder to combat. There are legitimate and well-founded reasons for these concerns, especially in rural, poor and minority communities. The cost/benefit analysis doesn’t exist for these people because they can’t know what’s true and what isn’t. Furthermore, establishing trust takes years and varies from person to person. The current approach utilizes community leaders and trusted individuals to advocate for the vaccine, typically at the local level because every community is different. Vaccine drives, celebrity endorsements, and growing public acceptance help, but overcoming mistrust is not easy. For example, how would you convince someone that the dose they’re receiving is actually the same one that everyone else is getting? Addressing trust issues takes a lot of time and effort. Providing adequate resources to the groups and people taking on this monumental challenge who typically don’t have them at their disposal will make a substantial difference.

Finally, let’s talk about politics. Republicans are overwhelmingly less likely to get vaccinated and more likely to believe conspiracy theories about the danger of vaccines. It doesn’t help that those attitudes were quickly normalized at a national level by supporters of President Trump, who probably deserves more credit for vaccine development than he’s gotten, but was hesitant to speak out against his base in an election year. It’s also the result of a party that has built a following stoking mistrust in government and embracing conspiracy theories. However, the question is how much of this type of concern is legitimate and how much is political theatre. How many people might publicly push the idea that vaccines are evil but then privately get vaccinated when it benefits them? The true believers will likely refuse the vaccine anyway, so the percentage of solely politically driven vaccine-hesitant people is probably very small. Regardless, it would help if the leaders of the party pushed back on this type of misinformation. The decision has already been politicized for these people, so they’ll take their cue from those they identify with.

There’s one final group of people to consider. Those who received their first dose and skipped their second. The CDC estimates that around 5 million people are in this category. Some of them may get it eventually, but most probably won’t. The people who had their second appointment canceled will likely reschedule, but the people who are afraid of the potential side effects or think that one dose is adequate might not. We’re still unsure how much protection is afforded by only one dose, but this issue highlights the main benefit of a one-dose vaccine, like Johnson and Johnson, especially for hesitant people. Convincing someone to get one shot is a lot easier than convincing them to get two. It’s a shame then that trust in that particular vaccine took such a hit.

For all types of hesitancy, media coverage plays a crucial role. By definition, the things that are newsworthy and draw attention tend to mislead the public. Responsible journalistic outlets will balance the news and the facts, but there are no gatekeepers left in the media. That’s why decisions like pausing the distribution of a vaccine matter so much; the headlines look bad and have a tangible negative impact on public health. Communication ahead of time is critical. Public officials get in trouble when they assume the intelligence of their audience. Pushing for everyone to get any vaccine as soon as possible while also reiterating that nothing changes for vaccinated people might be the safest message, but it isn’t very effective. Trying to downplay the 5 percent risk that comes with 95 percent efficacy results in people being surprised when vaccinated people get sick and/or die. And focusing on a couple of areas where cases are surging instead of highlighting the steep declines everywhere else results in unfounded fear. Even if the media won’t follow suit, public officials would benefit from telling a complete and nuanced truth and trusting their audience to correctly interpret it, rather than trying to spin the truth towards a larger objective.

Regardless of why people are hesitant to get vaccinated, making the process more convenient is a sure-fire way to get better results. Making that barrier as low as possible and minimizing the cost for as many people as possible should get easier as demand continues to drop. But if that’s not enough, further incentives and concentrated local efforts will be required, or else we might need to move the goalposts from herd immunity to normalcy with COVID-19 as an additional endemic disease.

…

To listen to the podcast or get additional facts and resources on this topic, go to Podcasts – Explain The News (April 26, 2021)

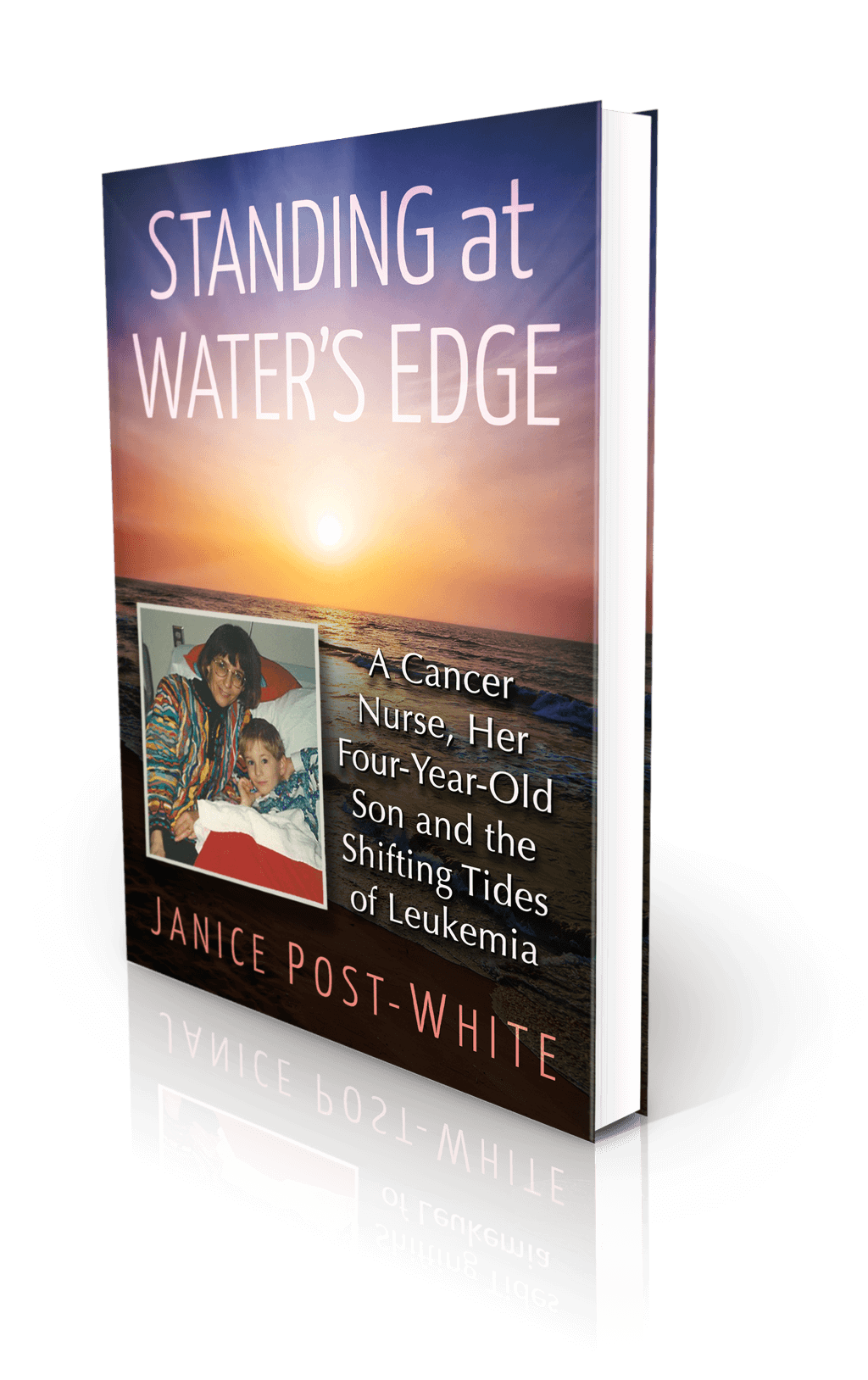

About the Book

Janice Post-White’s memoir is a story about a cancer nurse who thought she knew what life and death were about.

Then her 4-year-old son got leukemia.

This heart-wrenchingly real but inspiring book shines a light on the life-affirming discoveries that can be made when one is forced to face death—and bravely chooses to face fears.

ON SALE DECEMBER 3, 2021

2022 First Place Award from the American Journal of Nursing Book of the Year in the category of Consumer Health and Third Place in Creative Works

Finalist in Health/Cancer from the American Book Fest Best Book Awards, the International Book Awards, and the Eric Hoffer Book Awards