Photo by Atoms on Unsplash

Most children with COVID-19 have mild illness, with 0.5 to 6.1% hospitalized in the U.S. The risks may be low, but the stakes are high. And the numbers aren’t important when it’s your child in the hospital bed.

REALITY

More than 1 million children have been diagnosed with COVID-19 in the United States. And that’s only the ones who have been tested. Many children go undiagnosed because they have no symptoms or mild illness. I get it—why put kids through an uncomfortable nasal swab if they “aren’t that sick?” Anyone with symptoms needs to stay home anyway.

Thankfully, severe illness in children with COVID-19 is rare. And yet, no one can predict which child will need a ventilator to breathe, who will be in the 11% to get seriously ill with multisystem inflammatory syndrome (MIS-C), or how many will suffer long-term effects of myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) or postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS).

It could be any child. It could be your child or your grandchild.

In last week’s podcast for CIDRAP at the University of Minnesota (Nov 12, 2020), Dr. Michael Osterholm reported that 17 children were hospitalized in Minnesota with COVID-19, 5 of them in the intensive care unit. This may seem like a small number, but the image of those mothers and fathers hovering over their child’s hospital bed, watching for every breath and any change, gripped my heart until I told myself to breathe. And it still does. I fervently hope their child is not alone—as many adults are—during this scary time.

I know the heartache, the worry, the fear. I still see my son in that hospital bed when he was four years old. He didn’t have COVID, he had cancer. Another “rare” life-threatening and life-altering illness in children.

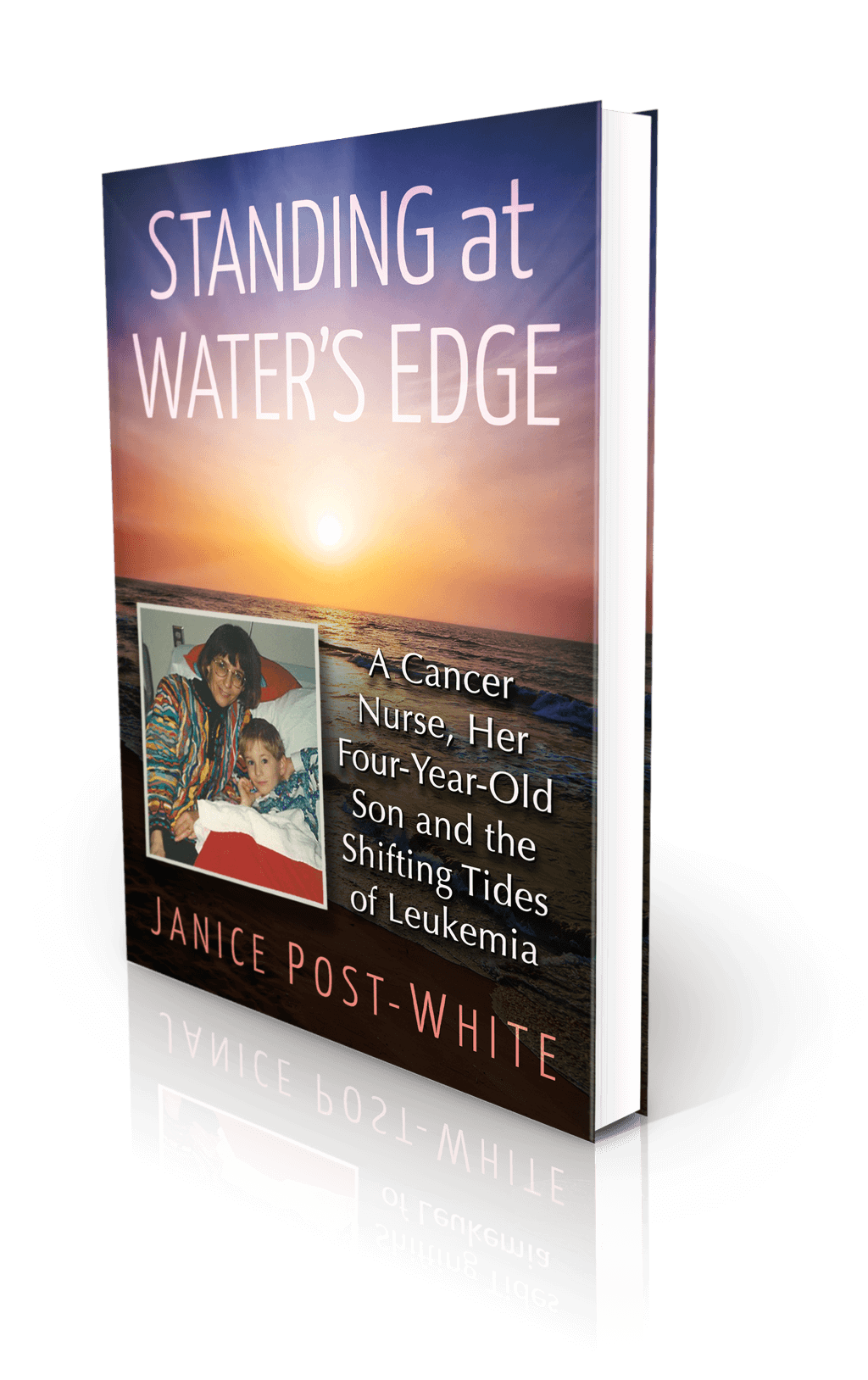

In Standing at Water’s Edge, I write:

Brennan was our first-born child, the one who determinedly came into this world at the exact stroke of the big hand on the twelve. It was as if he had emerged precise, focused, and ready for action. When he was just four hours old, in the soft light of night, I awoke to find him watching me from his bassinet. His large, quiescent eyes observed me lying on my side, facing him at eye level, hands tucked under my head and denting the goose down pillow encased in vibrant red, pink, and blue impressionist flowers.

His eyes didn’t question, they didn’t ask, they didn’t show. My newborn tranquilly watched me watching him. In one of those rare moments in an entire lifetime, he had caught me sleeping and I had caught him dreamily just observing. The silent serenity warped time.

Four years later, he was the one dwarfed in the hospital bed, with his red and black Mickey Mouse pillow tucked under his pale, sunken cheeks and vacant blue eyes, his faded blankie with sailboats and his mouse buddy dependably by his side. The transformation from one hospital visit to the next created a chasm so deep I feared looking back.

Images have a way of slinking in and descending the stairs to the past.

RISK

Cancer and COVID-19 are different. COVID-19 is a highly infectious disease caused by a virus; cancer is not contagious and is predominantly caused by genetic mutations and environmental predispositions/exposures. Many more children will get COVID-19 this year (> 1 million in the U.S.) than cancer (about 17,000), and more will survive COVID-19 (133 deaths thus far, compared to approximately 2,500 from cancer). But both COVID-19 and cancer are devastating diseases that can be life-threatening and life-altering.

The most important difference between cancer and COVID-19 is that COVID-19 is preventable; cancer in children is not. As a communicable disease, it is possible to avoid getting COVID-19. Although with rampant spread in the community, the risk of getting sick escalates with every interaction.

When my son was diagnosed with acute leukemia, I was a cancer nurse, educator, and researcher. But I was sideswiped by his diagnosis; I didn’t recognize the clues. After all, cancer happened to other people’s kids.

Day 1 in the hospital

After his diagnosis, I questioned our risk, including my exposure years earlier to pesticides in my home, radioactive isotopes in the lab, and chemotherapy agents in my work. Protections have improved over the years, but at the time, we took the only precautions we knew, often unaware of the risks. And even today, we don’t know the magnitude of those risks.

On the other hand, we do know what causes COVID-19 and what the risks are. For now, while we await vaccines, the only intervention is to avoid exposure to the coronavirus. But avoiding all human interaction is a drastic measure, especially when the risk extends month after month after month. Everyone is suffering from pandemic fatigue. We want to just live our lives.

Calculating and weighing the risks and balancing the potential consequences is tiring and tricky. Parents repeatedly ask, “Should I send my child to school if it’s an option? What’s the risk of bringing in outside caregivers, friends, or playmates? Are team sports or playgrounds safe?” We make choices every day as circumstances change and we do our best to adapt.

Although not everyone has options, those of us who do need to make careful and considerate choices. I continually ask, “Is this necessary or just desirable? Is there a safer alternative?” Avoiding the coronavirus is necessary, especially as cases—and hospitalizations and deaths—skyrocket through November into December.

In this week’s CIDRAP podcast (Nov. 19, 2020), Dr. Osterholm pays tribute to Bethany, a college student aspiring to be a child life specialist. Despite requesting and getting a private dorm room and bathroom and wearing a mask and social distancing in class, Bethany contracted COVID-19, presumably from a classmate who coughed throughout an in-person lecture. A few days after falling ill, Bethany died from a pulmonary emboli, a blood clot in her lungs.

None of Bethany’s circumstances were extraordinary. It could happen to anyone. That’s how careful we have to be to protect ourselves and others.

HOPE

Give yourself credit. You have survived some form of lockdown/restriction/isolation at home for at least eight months, and longer if you live in Europe or Asia. With highly effective vaccines projected for early distribution by the end of the year, we have hope for fewer cases, less critical illness, and fewer deaths. And eventually, less risk.

And yet, Pfizer and its European cohort, BioNTech, just recently started enrolling children as young as 12 years of age in its trials. Moderna and AstraZeneca also have forthcoming vaccines, but at this point, they have been tested in adults only. Even if the FDA approves emergency use authorization of the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines in December, it will be many more months before safety and efficacy of an appropriate dose for children is confirmed in a study trial. Will a vaccine be ready for them by the time they start school in the fall of 2021? And how many children will get it?

The world is making progress—there are many more vaccines being developed and tested in the United States and other countries. China and India have Phase I/II trials that include children as young as age 6. We need to hang in there through this recent surge in illness. There is a light at the end of the tunnel. For now, though, protecting ourselves and our children is still up to us as individuals. Everyone knows what to do—social distance, mask when out of your home, wash hands and common surfaces frequently, and stay home when you can. You are safer there.

Knowing what to do doesn’t always transfer to doing the right thing. Many factors go into someone’s decision to adhere to recommendations. Judging others according to our own criteria fuels anger rather than motivation. Like driving defensively, we take responsibility for ourselves (and our vehicle), and we stay alert to avoid the other guy who isn’t. The risk may be low, but the stakes can be high.

We couldn’t avoid cancer; we can avoid COVID-19. We can do this. For our children.

About the Book

Janice Post-White’s memoir is a story about a cancer nurse who thought she knew what life and death were about.

Then her 4-year-old son got leukemia.

This heart-wrenchingly real but inspiring book shines a light on the life-affirming discoveries that can be made when one is forced to face death—and bravely chooses to face fears.

ON SALE DECEMBER 3, 2021

2022 First Place Award from the American Journal of Nursing Book of the Year in the category of Consumer Health and Third Place in Creative Works

Finalist in Health/Cancer from the American Book Fest Best Book Awards, the International Book Awards, and the Eric Hoffer Book Awards