Sculpture of girl’s face evoking past and present, familiar and unfamiliar. Mark Manders, Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, MN

This week, the world surpassed 33 million cases of COVID-19 and 1 million deaths, with 7 million cases and 205,000 deaths in the United States. With just over 4 percent of the world’s population, the U.S has almost 21 percent of the global cases of COVID-19. How do we make sense of all these numbers?

One million deaths are hard to comprehend and impossible to relate to, unless, I imagine, you’ve been on the frontline caring for thousands who take their last breath on your shift. As a data person and researcher, I’ve been watching the number of deaths approach this milestone for a week. It was inevitable, expected. Although the daily confirmed cases are lower in some countries, they are rising again in other countries. The curve has not flattened. Not enough. Deaths will continue to climb. Each death is one too many.

Do you know anyone who has died from COVID-19? How do we give numbers meaningful context when each one represents a loved one, family member, friend, colleague, auntie, nana or papa, or tragically, a child or young adult? How do we keep perspective as we go on living our lives altered by new routines and limitations and worrying over our health and that of our loved ones?

The Bigger Picture

It’s hard to view the big picture when we are still mired in the details of changing circumstances (reopened schools and businesses, reduced restrictions) that are triggering new cases and escalating deaths. We are nine months into a pandemic that foreshadows an equivalent timeline of at least another nine months of uncertainty and unpredictability.

An estimated 50 million people died after 18 months of the 1918 Spanish flu (also a novel and new virus causing a pandemic). In comparison, one million people have died nine months into the COVID-19 pandemic.

Comparison of current COVID-19 to Spanish flu cases and deaths

| United States | Worldwide | |

| COVID-19 (9 months) | ||

| Cases (confirmed) | 7 million | 33 million |

| Deaths (attributed to) | 205,000 | 1 million |

| Spanish Flu (18 months) | ||

| Cases (estimated) | 28 million | 360-500 million |

| Deaths (estimated) | 350,000 – 675,000 | 50-100 million |

As of September 30, 2020. Numbers of COVID=19 cases/deaths rounded for easy comparison.

According to science journalist and author Gina Kolata, one in five people globally came down with the Spanish flu, including 28 percent of Americans. Other sources estimate one-third of the 1.8 billion population fell victim 1918-1920, with the number of deaths ranging from 50 million to 100 million globally and 350,000 to 675,000 Americans. The true number of Spanish flu cases and deaths will never be determined as there was no test in those days to confirm who had the H1N1 virus.

Thankfully, we aren’t there yet. However, at this time, according to the data we have, almost 3 percent of those who get sick with COVID-19 die. This is comparable to the Spanish flu, which killed an estimated 2.5 percent of its victims. This means that the Spanish flu and COVID-19 are 25-30 times more deadly than the typical annual influenza that kills 0.1 percent.

I am aware that this data doesn’t differentiate by age or conditions and will become outdated as each day ticks by. And, yes, inaccuracies exist. Even in an era of big data, extensive number crunching, and more sophisticated healthcare than a century earlier, we didn’t count everyone, we didn’t test everyone, some died from multiple causes, and many died without ever being tested.

We can select the data to showcase the point we want to make, but the bottom line is true and unalterable. One million persons, who were known and loved, died of COVID-19. At least one million.

Where Are We Headed?

When they first appeared, neither virus had diagnostic tests, treatments, or vaccines. The Spanish flu ended when those that were infected either died or developed immunity and the virus mutated. A century later, and only nine months into the pandemic, we have at least seven COVID-19 vaccines in Phase III clinical trials (testing effectiveness to prevent illness) and an estimated 200 more in development. Meanwhile, treatments are being tested to target and stop the virus from replicating in the body, calm over-reactive inflammatory immune responses, and lessen complications. A century after the Spanish flu, we are armed with data on the single-strand RNA sequence of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, we have experience with similar recent coronaviruses (MERS and SARS-CoV-1), and we have a global network of collaborating scientists, epidemiologists, practitioners, and public health advocates. There is hope.

And yet, we are far from herd immunity. According to three epidemiologic modeling teams at Harvard, the University of Minnesota, and the Covid-19 Projections website, only 10 percent to 16 percent of Americans have had the virus, leaving up to 90 percent of the population vulnerable. Even smaller percentages of antibodies were found in those donating blood to the Red Cross (2%) or undergoing dialysis (1%).

The United States has the highest worldwide case incidence and death count, with the Midwest states currently leading a resurgence. Minnesota (my home state) and our surrounding states are experiencing “uncontrolled spread.” Minnesota, an “orange alert” state, is surrounded by “red flag” states with active outbreaks, including North and South Dakota, Iowa, and Wisconsin.

Several of my health care providers restrict me from leaving the state. If I cross the border to visit my 90-year-old mother or see other family, I am not allowed in their clinic for 14 days. I would not be able to get my weekly infusions, one of which replenishes the antibodies my body fails to make to protect me from viruses and bacteria.

Although I believe I am more at risk going to the grocery store in my urban area, I try to keep perspective by believing this restriction is temporary and necessary and is meant to protect both me and others in the immunology, pulmonary, and rheumatology clinics. Stepping back from my own circumstances to consider the greater good for all and the need for guidelines gives me perspective and patience to endure. And I know I am safer at home. We all are.

Stonehenge Autumn Equinox Sunrise By C.J. Everhardt, Shutterstock

As we pass through the fall equinox in the northern hemisphere, the days are equally balanced between night and day. We accept (often begrudgingly) the shorter, darker days. Autumn has arrived, and winter will follow, but spring will come. We acknowledge the dark while anticipating the light. The pandemic may feel like the longest darkness you have ever endured. But it, too, at least as we know it, will end. Seek stillness in the dark while awaiting the light.

Wishing you health, peace, and perspective,

~ Janice

About the Book

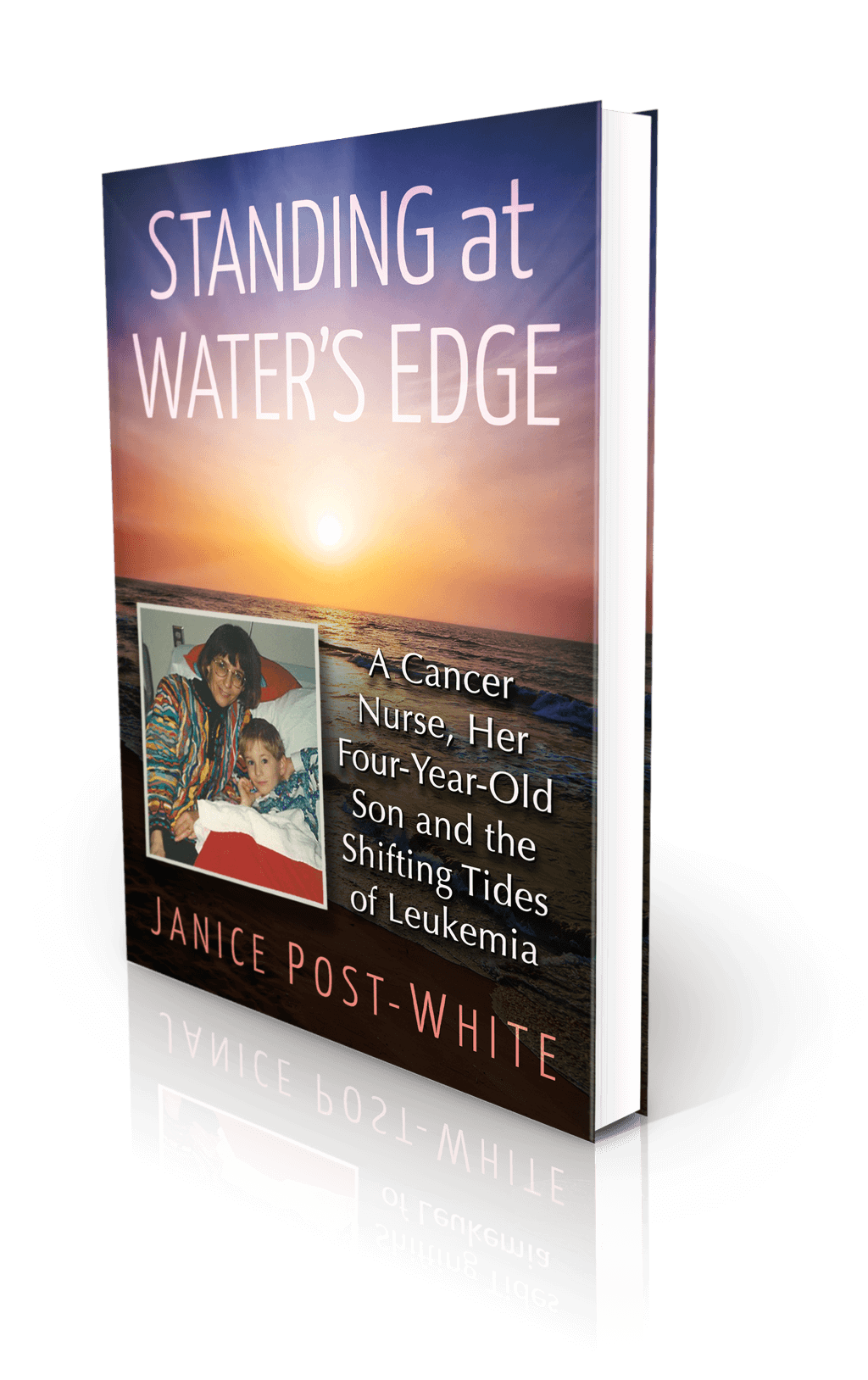

Janice Post-White’s memoir is a story about a cancer nurse who thought she knew what life and death were about.

Then her 4-year-old son got leukemia.

This heart-wrenchingly real but inspiring book shines a light on the life-affirming discoveries that can be made when one is forced to face death—and bravely chooses to face fears.

ON SALE DECEMBER 3, 2021

2022 First Place Award from the American Journal of Nursing Book of the Year in the category of Consumer Health and Third Place in Creative Works

Finalist in Health/Cancer from the American Book Fest Best Book Awards, the International Book Awards, and the Eric Hoffer Book Awards