Shutterstock by Peshkova

My twin died six years ago this week. His death was sudden, unexpected, a surprise to us all. He thought he had our paternal grandparents’ genes—Grandpa died after a stroke at 97 and Grandma (92) died suddenly four months later, after telling us grandkids that she couldn’t live without Grandpa. No one really thought about our maternal gene pool; both of those grandparents died before we were born.

It’s natural to cling to what we know and what we want to believe. We create our own reality in our mind. Our head often ignores or overrides what our heart tries to tell us. Closing our mind closes off our heart.

Despite inheriting longevity genes from both of his parents, our father died of heart disease and lung cancer at age 83. His trim frame and athlete lifestyle couldn’t compensate for fifty years of smoking. But my brother Jerry had never smoked. He exercised vigorously six days a week, ate vegetarian and often dairy and gluten-free, and he never drank caffeine and rarely consumed alcohol. We rationalized away his risk.

Jerry biked 54 miles on Saturday, rested on Sunday, and collapsed in his office after biking to work on Monday morning. He died with “severe coronary arteriosclerosis.” Blocked coronary arteries. He was in such conditioned shape—his body compensated until it could no longer.

My brother died the way he lived, full of life and vitality, strong and determined, ready for the next adventure. If only he had listened to his heart.

He didn’t ignore the shortness of breath that summer; he tried to figure it out. “After four or five minutes into biking, running, or swimming, I have to stop, cough a few times, and take a deep breath,” he told me. “And then it goes away.” He pushed through it. After all, asthma ran in our family, and he had had a cough after a viral cold that summer. No one—not him, not his two doctors, nor his sister the nurse, suspected his heart. I expect the emergency room staff would have if he had gone in.

I certainly was not the impartial caregiver he needed; one who assessed objectively and checked off an algorithm of symptoms and risk. I shared at least some of his genes and from what I can tell, a lot of his psyche/mentality. We both were professors of thinking. We created analytical models and mined data. He, in the field of econometric modeling and management information systems; me, in clinical and laboratory research testing psychoneuroimmune signaling between the body, mind, and spirit. We had too little data on his condition in which to draw conclusions. And then we ran out of time.

It’s easy to ignore symptoms that go away. We want it to be nothing big, nothing life-threatening. That’s what I had believed years earlier in the two months leading up to my then four-year-old’s diagnosis of leukemia. I’m an oncology nurse, and I didn’t suspect cancer in my son or heart disease in my twin. I might have been too close and too afraid to see clearly. Regret and guilt set in all over again.

I’ve learned through these experiences, and I eventually let go of the guilt. My brother was a teacher; he taught me as much in his death as he had in his life.

I learned

- that it’s important to pay attention—to let go of my own agenda, preconceived answers, assumptions, distractions.

- to ask questions and then to listen for the answers. Really listen. It’s easier said than done, and some responses aren’t in words.

- to stay open to both thoughts and feelings, and to listen with my heart as well as my head.

- to stop

trying to figure everything out by myself.

Signs

On our first trip to his house after his death, I was surprised to find yellow post-it notes scattered around the desk in the sunny corner of his kitchen. I create thoughts in the same way. Two of his verses took my breath away. (I have to trust that he wouldn’t mind my sharing them if they have something to say, to teach).

“I wanna go ho ho ho back home

Don’t you wanna go ho

oh o o home…”

o o o o _____

“Horns we blow

Dogs we curse

Down below

Rolls the hearse

And we’ll all go sliding

All go sliding…”

Was his subconscious processing what his heart already knew? Was he aware of his risk on some level, but afraid to share his fear? Was I not tuned in to what he wasn’t saying, as much as to what he was telling me? Of course, he didn’t have any obligation to share his thoughts or his feelings with his sister, even a twin.

After his death, I realized how many times we had connected spiritually without ever saying a word. I would ask without voicing, How are you really doing, Jerry? and I would just know. Words weren’t necessary. But I didn’t really process this ethereal connection in the moment. It just felt natural. But that was when we were together, in the same room. All of our conversations that summer had been over the phone.

Shutterstock by Romolo Tavani

From the afterlife

We talk a lot now. It’s not the same—I miss hearing his voice, his hearty and joyful laugh, his tolerant inquisition of my unconventional thinking. I’d love to hear his thoughts on the coronavirus pandemic…I can’t guess at that. But I still ask for his advice and feel his answers. After six years and several connections through mediums, I feel as if I know his spirit self differently than his earthly self. He responds from a different mindset; one he calls his “bigger mind.”

His immediate response to my first connection with him through a medium, two months after his passing, was, “What took you so long?” He had a lot to say.

As I said to his graduate student that first day in Jerry’s empty office, “When you need direction, ask, “What would Dr. Post say?”

Asking—and listening—to what your loved one would say is getting advice from someone you know who loves you, cares about you, and has your best interests in mind. Most of us have subconsciously heard a parent’s words of advice when they weren’t with us in person. Psychologists call this “perspective-taking.” Asking and listening gets us out of our head and back in touch with our heart. And it keeps us connected, even if our advisor is across the veil.

My brother’s death was a wake-up call to heed the heart—physically, emotionally, and spiritually. Jerry tells me now from his spirit world to “lighten up,” laugh more, get out in nature, and enjoy being human. The medium (and Jerry) didn’t mention anything about a pandemic, the reality so many of us are just waiting to get over with so that we can enjoy life again.

Create your own reality

It’s hard to lighten up right now, but life marches on, with or without COVID-19. It’s also true that our individual perceptions shape our reality. What we tell ourselves to be true becomes real in our mind. For example, memories get shapeshifted when we selectively recall events from our unique perspective. We zoom in on what’s meaningful to us. Someone else, also present, may remember things differently.

Our perceptions—what we believe and expect—become our reality. Which means that we have the ability to reshape the reality we’ve created in our mind. Neuroscientists call this “neuroplasticity.” And we can use it to our advantage.

To retrain negative perceptions, His Holiness the Dalai Lama advises us to wake up telling ourselves “I wish for a happy day.” No one wakes up wishing for trouble, he says. We can cultivate countermeasures, as he calls them, to retrain how we perceive our reality. One way to do this is to view situations from more than one angle, more than one dimension. Instead of responding to the chatter in our head that convinces us of one solution, one belief, we can broaden our perception by thinking of a situation from different angles or dimensions. Think from “three dimensions, or four dimensions, or six dimensions—then you get a clearer picture of reality,” His Holiness says.

Perhaps this is what we do when we use empathy to see things from someone else’s perspective, when we weigh the pros and cons of a decision or action we are considering, and when we consult our feelings and intuition in addition to our thoughts. We get new insight and clarity as we expand our perspective and view the situation from many angles, not just the first one that pops into our head or the one we want to believe is true.

I call this “all ways of knowing.” Consulting my twin through a medium or via my own expanded consciousness empowers me to see from a broader perspective, a bigger mind.

We can cultivate these “countermeasures” through practice. “Take small steps,” the Dalai Lama recommends, “One minute counts.” Start with ten seconds, one minute, then expand to five, ten, and twenty minutes. Expanding awareness, consciousness, perception is a practiced skill. After a while, he says, we start to become familiar with and habituate to our expanded reality and our perception of who we believe ourselves to be. (His Holiness shares these specific teachings in 2008; 9.36 and 36.07 minutes).

This insight into the self is one element of the four pillars of well-being, according to Dr. Richie Davidson, a neuroscientist at the Center for Healthy Minds at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. Click here to learn more about the four pillars (awareness, connection, insight, and purpose) and the science behind them, or here to access free practices and tools to enhance well-being.

How we see the world and our place within it is a reflection of ourselves and our connection to others, to humanity. At this anniversary of my twin’s death, I needed to feel his love and his compassion and kindness. Reaching out to others, wherever they may be, gives us perspective and a connection beyond ourselves.

Shutterstock by Wollertz

Thank you for being there for me, Jerry. My heart still beats with love.

And now I need to go work on my “happiness-during-pandemic” perspective-taking.

Namaste,

Twin B

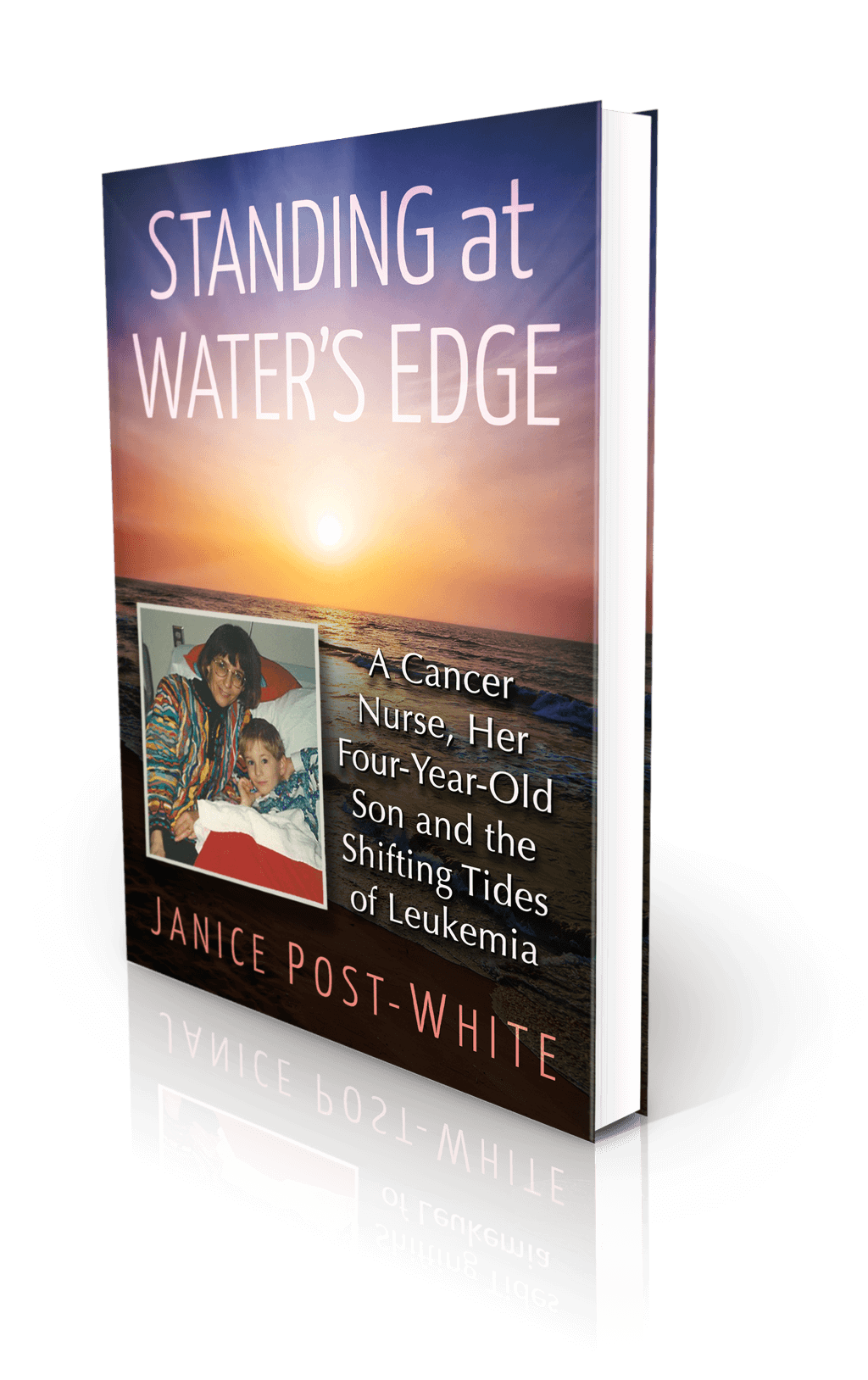

About the Book

Janice Post-White’s memoir is a story about a cancer nurse who thought she knew what life and death were about.

Then her 4-year-old son got leukemia.

This heart-wrenchingly real but inspiring book shines a light on the life-affirming discoveries that can be made when one is forced to face death—and bravely chooses to face fears.

ON SALE DECEMBER 3, 2021

2022 First Place Award from the American Journal of Nursing Book of the Year in the category of Consumer Health and Third Place in Creative Works

Finalist in Health/Cancer from the American Book Fest Best Book Awards, the International Book Awards, and the Eric Hoffer Book Awards