istockphoto by stereohype

“Have no regrets” my friend murmured after I shared my angst over decisions I faced as my father approached death. That was a decade ago, and I’ve been mulling over regrets ever since. Is it even possible to live life without the remorseful “I can’t believe I did/said that” torment we inflict upon ourselves? And how do we move on from this all-too-human self-criticism?

I revisited regret this week. For my writing class, we were to write a scene in which a character does something despicable and then rationalizes his actions. I take my homework seriously—even after all these years—and I contemplated the assignment all week. Despicable is such a strong word, an intense feeling. Even synonyms—disgusting, disgraceful, loathsome, abhorrent—didn’t shed light on a situation or event for me. I couldn’t relate. My emotions are more grounded and deliberate, compliments of a birth moon in Taurus. Plus, I learned early on how to hide my feelings, even from myself.

I don’t write fiction. I write memoir and nonfiction, which means I write truthfully, honestly, with heart and soul. And without imagination. I’m often the main character, facing off against my own thoughts and analyzing my interactions with others. The conflict is internal, the plot emotive, rather than actionable. I don’t let go of things easily (another Taurus moon attribute), so I write to reexamine my thoughts, feelings, and interactions in order to make sense of them. I write to understand. Then I can let go and move on. Unless it’s unbearable and I rationalize the whole situation, wrapping an excuse in a neat little story I tell myself. Then I carry the regret subconsciously because I swaddle it in a temporary comforter rather than processing it and letting it go.

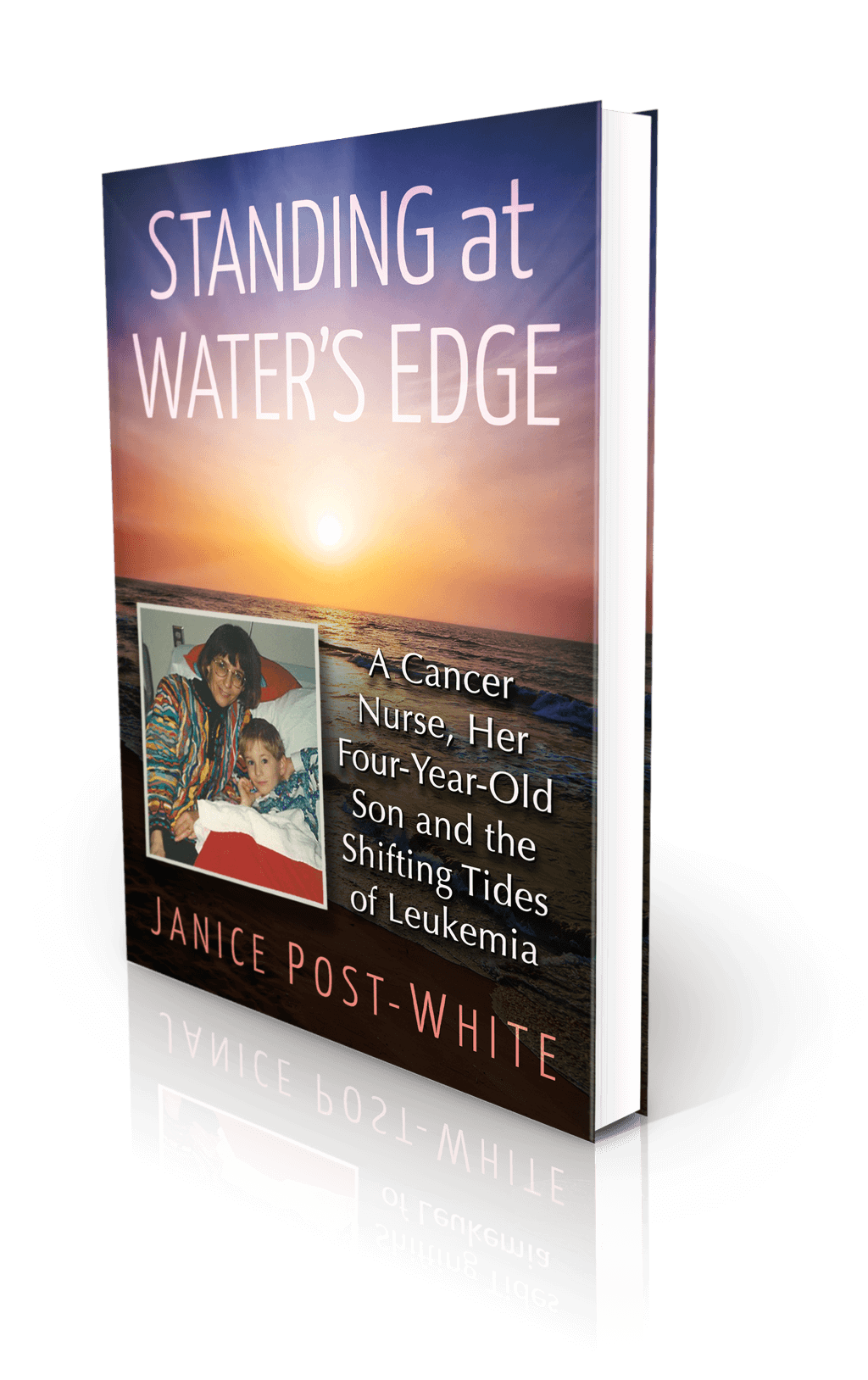

And that’s how I redefined the assignment for myself. I couldn’t admit to my own despicable actions, but I understood regret. I searched my forthcoming book, Standing at Water’s Edge, for “regret” and “rationalized.” I chose one of the four scenes to adapt for class. It was easier than diving deep into that emotional abyss all over again. I’ll have to read it to my peers, which means I’ll have to revisit the scenario once again. But they will be critiquing the craft, not me, the narrator. Which makes me want to amplify the drama to make it more captivating. But I don’t. I let my actions and analytical rationalization speak for themselves.

The scene may not convey “despicable” to the fiction writers in class, but to me, the mother who hovered over her four-year-old son lying flat on the cold, hardwood floor in the kitchen on a subzero day outside, determined to get that bitter-tasting liquid medicine into his sick but protesting body, it feels horribly regretful and reproachable. And that’s what matters. I am the narrator, the character, and the instigator of despicable action.

I relived the regret, the wish to do something different, the desire to forget the whole situation. And yet, I still understood her actions. She desperately wanted to save her son. She had tried everything she could think of at that moment.

Of course, I can see the situation more clearly twenty years later. It’s there in black and white on paper. I can no longer edit reality. Writing about it and revisiting it years later has uncovered the underlying fear I had rationalized away. I had wrapped it up in justification, a blanket to soothe my soul. Sometimes, when the front door is locked, we get in through the back door.

“I had buried my regrets for years, acknowledging them only when they surfaced in my dreams. Guilt and regrets aren’t all bad. They motivate us to change, to do better next time. But dwelling on the past can get us stuck. It was time to move on. I had to learn from them, not learn to live with them. I practiced forgiving myself in the shower every day.”

Standing at Water’s Edge, Chapter 28. Letting Go

Moving On

Feeling regret isn’t all bad. It can motivate us to change. If we own it.

Overlooking the unsettling feeling or behavior, sweeping it under the rug of consciousness, is “pseudo-self-forgiveness” according to Kendra Cherry, who outlines The 4 R’s of self-forgiveness:

- Responsibility: Own/acknowledge the feeling, thought, action and move beyond rationalizing, justifying, making excuses.

- Remorse allows us to see clearly, and when we see things clearly, we are moved to act.

- Repair and restore trust: Apologize, ask for forgiveness of others, of yourself.

- Renewal: Learn from the experience, then move on from its grip.

Okay, I think, I’ve got this. Now that I own and accept my regrettable behavior, I can learn from it and move on. But how? I may be good at analyzing a situation, learning from it, and strategizing a different outcome for the next time, but I get stuck at forgiving myself. It’s easy to promise but hard to do.

Kira Newman says that forgiving yourself requires more than just putting the past behind you and moving on. It is about accepting what has happened and showing compassion to yourself.

Which, according to the self-compassion guru, Kristin Neff, requires acknowledging and accepting that we are imperfect and vulnerable humans. Showing ourselves compassion means accepting our actions and experiences, embracing ourselves with warmth and tenderness, and forgiving ourselves.

We humans make mistakes and have regrets, despite our best intentions. I hesitate to label regrettable actions as mistakes, because I believe mistakes are our best teachers, and hence are not the opposing wrong to the right. We learn more from our mistakes than we do from our successes. And isn’t that what we are here for–to learn from our experiences?

***

I’m reminded of my assignment. Why are we writing about anyone’s despicable or regretful actions? Is this assignment an exercise in drama or showing versus telling? Novelists freely infuse tension, suspense, and conflict into their story by creating despicable actions for their characters, while memoirists have to dig deep within to recall painful events and feelings—and then share them. Why would we do this when it’s hard enough to admit our weaknesses to ourselves? Maybe because we learn something about our motivations; maybe because heartache is relatable.

Whether fiction or nonfiction, imagined or real, the reader relates in some way to the characters’ struggles and triumph. When we embrace our vulnerability, imperfections, and humanity, we feel connected. We are not alone. Reading stories of how others show compassion, forgiveness, and resilience in the face of adversity also gives us perspective and can teach us new ways of responding. We learn from our experiences and from each other.

I write memoir to understand and make sense of my experiences. I read memoir to learn from others and see my humanity mirrored in theirs. Although circumstances differ, regrets are universal.

Be the best you can be.

About the Book

Janice Post-White’s memoir is a story about a cancer nurse who thought she knew what life and death were about.

Then her 4-year-old son got leukemia.

This heart-wrenchingly real but inspiring book shines a light on the life-affirming discoveries that can be made when one is forced to face death—and bravely chooses to face fears.

ON SALE DECEMBER 3, 2021

2022 First Place Award from the American Journal of Nursing Book of the Year in the category of Consumer Health and Third Place in Creative Works

Finalist in Health/Cancer from the American Book Fest Best Book Awards, the International Book Awards, and the Eric Hoffer Book Awards