Sand sculpture of Bubonic plague. Bouke Atema. istock.com

How do we get through the COVID-19 pandemic? Lately, I’ve been compelled to read stories about how others have survived something. The circumstances are less important to me than how they got through—how they responded to and managed unexpected and uncontrollable adversity. Did survivors of other pandemics, wars, or adverse childhood experiences rise to the occasion with strength and resilience to do what needed to be done, or did they retreat to a familiar comfort zone to calm their fears and anxieties or rely on others to help them get through? How did they deal with the chaos and uncertainty? Fear is a human condition, and survival is a human instinct. We feel compelled to do something.

We are all unique in our responses; one strategy is not better than the other. What I do to cope might trigger anxiety in you. So, how do we keep grounded in reality and stay consistent with who we are and what we value? As Kate Bowler, author, historian, professor, and stage four colon cancer survivor, so eloquently poses in her August 2020 “Everything Happens” podcast with clinical psychologist Ken Carter, “How do we live authentically inside the limits that we’re given right now?”

Although the COVID-19 pandemic might be novel and new—inciting both our naïve immune system and our fear-driven psyche—our response is likely familiar. We are creatures of habit. We tend to fall back on whatever strategy worked in the past (or sometimes didn’t, but it’s all we know). After reading historical accounts and stories of earlier pandemics, I’ve realized that humans have quite similar emotional responses to crises, but we often have quite different strategies for getting through.

How Others Got Through

According to online and published historical records, people have been responding to pandemics for centuries with fear, panic, avoidance, blame, uncertainty, and confusion, as well as, I’m guessing, more positive responses that aren’t reported in historical documents. Why is it that we either selectively recall or cling to the negative circumstances in life? Reports of neighbors lashing out at each other, admonishing each other, or people turning inward and fretting about their own souls or sins, reflect both the uniqueness of human responses and the powerlessness we feel when confronted by a terrifying outcome we seem to have no explanation for or control over. Doing something, or even just understanding how an event came to be, can give us a feeling of control. But is that enough?

What helped our ancestors get through five centuries (1347-1900) of intermittent episodes of bubonic plague and two years of the most lethal pandemic ever recorded, the Spanish Influenza (1918-1920)? There are few personal accounts of their state of mind, but we know what they did. Quite surprising to me was their consistent, methodical response to:

– quarantine the ill from the well (40 days was the norm),

– social distance (windows were carved into buildings to sell wine during the Italian plague of 1629), and

– wear masks (physicians in particular wore masks during the bubonic plague of the 16th century).

These strategies reduced the spread of disease, even if they didn’t know why. Once germ theory was acknowledged in the mid-1800s, hand washing, hygiene, and open-air spaces were advocated. People opened windows in their homes (contradicting their former belief that outside air would bring in illness), and outdoor schoolrooms were constructed to keep children in school during the 1918-1919 Spanish flu.

And yet, controversy prevailed around these practices, just as it does today. The mayor of San Francisco reportedly wore his mask under his chin during the Armistice Day Parade (November 11, 1918), and thousands ignored social distancing and lined the streets to celebrate the end of WWI. Cases of Spanish flu skyrocketed shortly after (Pale Rider, by Laura Spinney, 2018; The Great Influenza, by John M. Barry, 2005).

In Hamnet (2020), Maggie O’Farrell writes a fictionalized, but historical, account of how William Shakespeare’s only son Hamnet might have died at the age of eleven from bubonic plague. (At the time of Hamnet’s death in 1596, death records did not report the cause of death, although bubonic plague has been speculated by others). In the book, Hamnet’s mother agonizes over how she could have been so preoccupied with saving his twin sister Judith that she missed the signs that Hamnet was pale, weak, and “ghostlike.” Hamnet dies, Judith survives, and the family grieves and moves on with life in unique ways. You can probably guess how Shakespeare coped with his only son’s death. (Hint: Hamlet was performed in London four years later).

O’Farrell’s personal experiences facing death no doubt inform her interpretation of what it could have been like for Hamnet’s family. In her memoir I Am, I Am, I Am: Seventeen Brushes with Death (2018), O’Farrell shows how courage, strength, determination, and gratitude help us get through life’s most fearsome encounters and not give in to fear. Michele Harper (The Beauty in Breaking, 2020) similarly dives into the hard stuff and demonstrates how knowing oneself, setting boundaries, letting go, and staying present to life, with compassion, helps us make sense of and get through situations of life and death.

Throughout this long and undulating COVID-19 pandemic, each of us is likely to use whatever strategies work to calm our fears, soothe our grief, distract us from ruminating over the past, restore a sense of routine, and keep us focused on the goal of getting through and keeping things as normal as possible. We are survivors. That’s what I keep telling myself, anyway. We’ve all been through something in our lives that required fortitude, strength, courage, perseverance, trust, faith—whatever it is we rely on to “get through” when life challenges us in unexpected ways. What got you through past misfortune? Is it helping you now?

Survival Mode

Back in March, when COVID-19 cases in older adults and persons with comorbidities far exceeded any other population cohort, I determinedly sprang into action to find and review our wills, draft password documents, and organize bills and files. What if our worst fear materialized and our sons had to “take over” for us? My laser focus was fueled by the contrived urgency of this happening “any day” or “tomorrow.” And for some, it did, including a friend and former colleague who died in early May after a “brief and aggressive attack” by COVID-19.

In my view, I was living from one life-preserving immune-antibody infusion to the next, treatments I’d been getting every three weeks for fifteen years. After each infusion, I would ask myself what I needed to accomplish in the next three weeks, and I set out to do the most important things first.

I had relied on this same strategy when my son was diagnosed with leukemia twenty years ago. I buried my emotions and flew into action. I called it “survival mode.” I put one foot in front of the other and followed the treatment roadmap adapting our lives to new routines and new identities. Setbacks reminded me of our vulnerability, and I learned to let go of my expectations and to accept help along the way. At the end of the first turbulent year of treatment, we entered a less aggressive “maintenance” phase that lasted an additional two years. Only then could I take a deep breath and reflect back on what we had been through and how we had survived.

Blocked path, Cedar Lake. Post-White

There is no roadmap for the coronavirus pandemic. No one really knows the trajectory it will take, the consequences we will face, or even the best strategies for treatment and survival. We are reacting when we are accustomed to forecasting. The uncertain future binds us to the moment, which is a good thing, if we can stay centered and manage the anxiety of not knowing.

Uncertainty

How long will we have to endure the uncertainty, the restrictions, the protective behaviors that have by now become quite familiar? How long will we have to be on guard against this potentially fatal or protracted illness? We are all tired of the isolation, change in our routines, lack of fun in our lives, monotony, missed events, loss of traditions and celebrations, disconnect with family and loved ones, and the stress of job changes and financial uncertainty. All the stuff of our daily lives is in limbo.

The first bubonic plague (The Black Death, 1347-1353) took six years to subside (can you imagine?), although subsequent outbreaks lasted one to two years, as did the Spanish flu. (Although two-thirds of the deaths from the Spanish flu occurred in the first twenty-four weeks). The SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) coronavirus and H1N1 influenza (Spanish flu) are different respiratory viruses, but they both appear for the first time and they share eerily similar symptoms and method of contagion, if not comparable trajectories. The only certainty is that many will die and social distancing works.

How did other pandemic survivors live with the ongoing uncertainty? I can only guess that they did what we are doing now—living in the moment, adapting routines, trying to prevent illness and take care of others, and just getting through the days, one step at a time.

As I reflect back on my son’s three years of treatment, I can see now that I got through by:

– Acknowledging my fears and emotions (but not dwelling on them)

– Letting go of expectations and what we lost (you can never go back to before)

– Focusing on the moment, thinking about how to best get through today

– Asking for and accepting help and support

– Saying “no” to protect my energy

– Helping others, thinking of others

– Trusting myself (and others) to do the best I/we could

– Being thankful for every day and celebrating the good times

Surviving leukemia didn’t end the uncertainty. Instead, it brought new fears of relapse and long-term and late-effects of treatment. But we moved on, reclaiming life and three years of childhood. As with anything, time and distance provide perspective.

What will we remember twenty years from now? Will we think about what we did to control the virus (or what we failed to do), how we responded (or didn’t respond), or the emotions (both positive and negative) that drove our actions and reactions during this time of crises? Will you be able to see how you survived, overcame, and got through the worst of times, and what you learned about yourself, others, and life?

We learn resilience throughout our lives—from family, culture, experiences, and opportunities. COVID-19 is just one of the circumstances challenging us to do the best we can as we live through the stress, uncertainty, and unpredictable path forward.

As Kate Bowler says, “Life is a chronic condition; there is no cure to being human. Living is deciding how to live alongside our fear.”

Sometimes it is enough to just get through.

~ Janice

About the Book

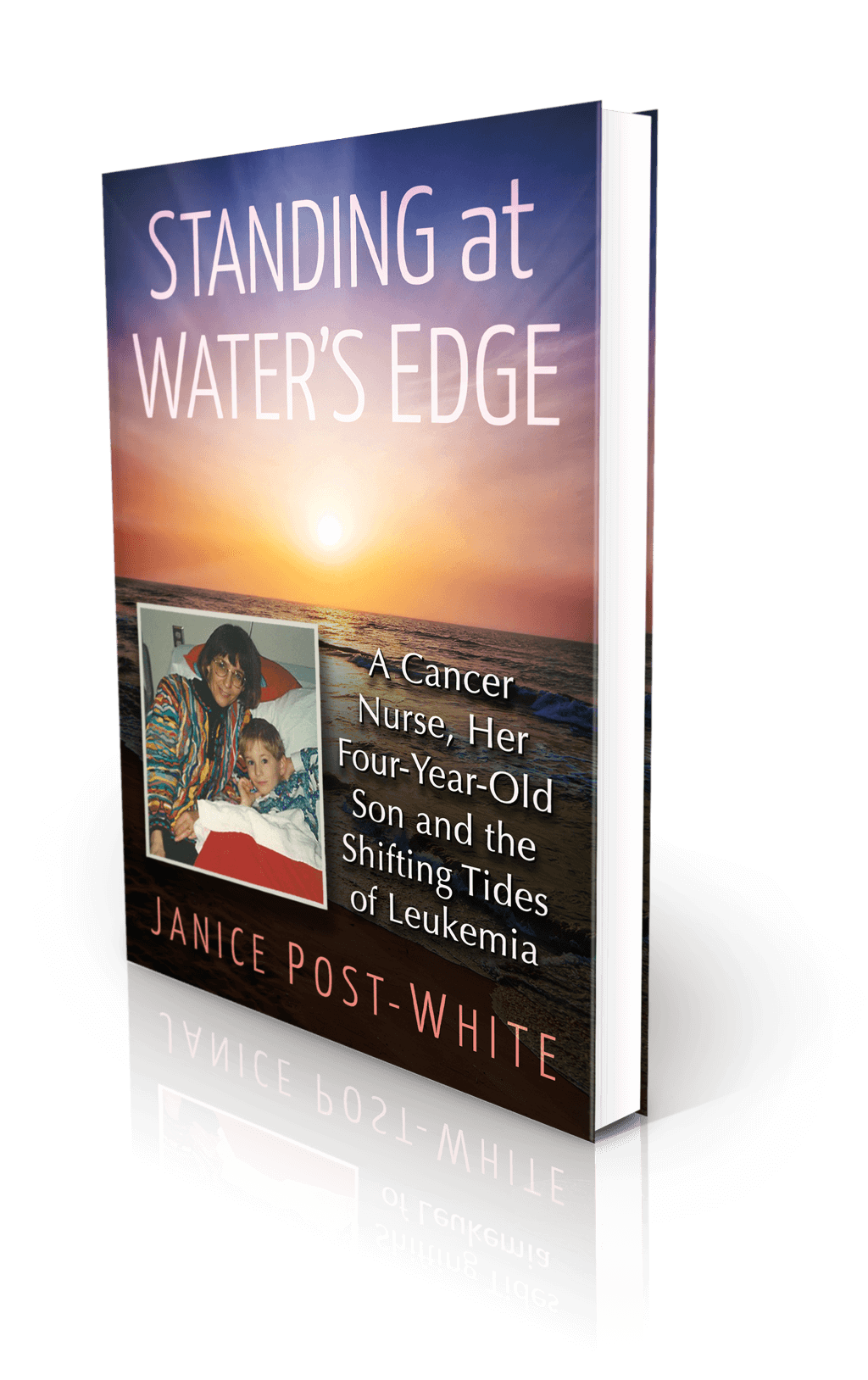

Janice Post-White’s memoir is a story about a cancer nurse who thought she knew what life and death were about.

Then her 4-year-old son got leukemia.

This heart-wrenchingly real but inspiring book shines a light on the life-affirming discoveries that can be made when one is forced to face death—and bravely chooses to face fears.

ON SALE DECEMBER 3, 2021

2022 First Place Award from the American Journal of Nursing Book of the Year in the category of Consumer Health and Third Place in Creative Works

Finalist in Health/Cancer from the American Book Fest Best Book Awards, the International Book Awards, and the Eric Hoffer Book Awards